June 15 Marks 6,000 Days of Guantánamo: Join Us in Telling Donald Trump, "Not One Day More!"

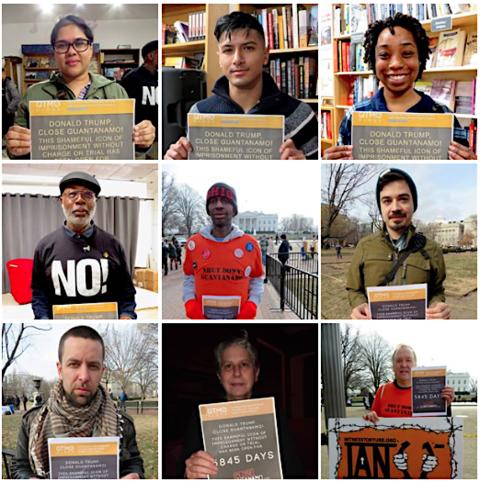

Some of the people who have called for Donald Trump to close Guantánamo in 2018, holding posters reminding him of how long the prison has been open.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work in 2018. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, June 6, 2018

Next Friday, June 15, 2018, is a bleak day for anyone who cares about justice and the rule of law, because the prison at Guantánamo Bay, where men are, for the most part, held indefinitely without charge or trial, will have been open for 6,000 days; or, to put it another way, 16 years, five months and four days. We hope you will join us in making some noise to mark this sad milestone in America’s modern history.

All year we’ve been running the Gitmo Clock, which counts, in real time, how long Guantánamo has been open, and in connection with that, we’ve made posters available every 25 days showing how long the prison has been open, and inviting suporters of Guantánamo’s closure to take photos with them, and to send them to us. The poster for 6,000 days is here. Please print it off, take a photo with it, ask your family and friends to do the same, and send the photos to us. We will add them to the photos we’ve been publishing all year, which can be found here.

How long is 6,000 days?

To give you some idea of how long 6,000 days is, try to remember what you were doing on January 11, 2002, when the prison opened. Perhaps you weren’t yet born, or perhaps, like me, you have sons or daughters who were just toddlers when those first photos of orange-clad, sensorily-deprived prisoners kneeling in the Caribbean sun as U.S. soldiers barked orders at them were first released. My son is now 18 years old — nearly 18 and a half, in fact — but he was just two when Guantánamo opened.

For anyone 16 and under, Guantánamo has been open their whole lives, and, in addition, for Americans and other NATO members like the U.K., our countries have also, unacceptably, been at war for their entire lives, mired in an unwinnable situation in Afghanistan, in which, as the author Anand Gopal explained to me several years ago, the U.S. actually snatched defeat from the jaws of victory back in 2002, when the Taliban fell and al-Qaeda were decimated, but the U.S. stayed on, out of its depth and played by whichever dubious lawlords succeeded in persuading them that they were their best friends.

I have been intimately involved in the Guantánamo story, researching and writing about it on an almost daily basis, for over 12 years now, beginning in March 2006. At the time, the prison had been open for less than 2,000 days. That milestone was reached on June 3, 2006, just days before one of the most shocking episodes in Guantánamo’s long and sordid history — the deaths of three prisoners, which the authorities described as a triple suicide, and "an act of asymmetrical warfare," but which other parties, including former U.S. military personnel who served on the base at the time, regard as probable homicides.

President Obama, who took office in January 2009 promising to close Guantánamo within a year, had already been in office for over a year when, still open, the prison marked its 3,000th day of operations, on March 29, 2010. 4,000 days also took place on Obama’s watch, on December 23, 2012, just three days after my son’s 13th birthday, and 5,000 days, on August 20, 2014.

Play this game yourself, if you like, and see what you can remember when — and then imagine being held in Guantánamo for all this time, without even being able to see any of your family members, even if they could get out to Guantánamo, because no Guantánamo prisoner has ever been allowed a family visit, unlike those convicted of the most horrendous crimes on the U.S. mainland.

Remember too that the total length of World War I and World War II was just 3,757 days (1,564 days plus 2,193 days), and yet the "war on terror" declared by the administration of George W. Bush, of which Guantánamo is a key component, has now been ongoing for over 6,100 days, with no sign that those with power and influence in the U.S. have any intention of acknowledging that a war cannot go on forever, and that it must be bounded in some way by time and place.

After 9/11, the Bush administration effectively declared the entire world to be a battleground in an endless war — an outrageous proposal, and yet one which Obama endorsed with his extra-judicial drone assassinations in countries with which the U.S. was not at war, and one which, of course, Donald Trump has also been free to interpret as he wishes.

Why Guantánamo must be closed

Conceived in the heat of vengeance following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the prison at Guantánamo Bay was, from the beginning, a dangerous aberration, turning its back on centuries of laws and treaties regarding the treatment of prisoners.

In countries that, like the U.S., claim to respect the rule of law, there are only two ways to deprive someone of their liberty — either as a criminal suspect, to be changed and tried without undue delay, or as a prisoner of war, taken off a battlefield, who can be held unmolested until the end of hostilities under the terms of the Geneva Conventions.

At Guantánamo, however, the U.S. invented a third category of prisoner — "enemy combatants," who had no rights whatsoever, and were taken to Guantánamo, a U.S. naval base on Cuba, so that they would be beyond the reach of the U.S. courts, and so that the U.S. authorities could do what they wanted with them.

In February 2002, George W. Bush issued a presidential memo specifically depriving them of the protections of the Geneva Conventions, and, sadly, for the next two years and four months, there was nothing to protect them from the torture and abuse that the U.S. authorities implemented, and which they also practiced in Afghanistan, and in Iraq, where, eventually, the Abu Ghraib scandal surfaced to provide an insight into what the "war on terror" really meant.

Over the years, lawyers fought back against the black hole that Guantánamo was at its founding, securing access to the prisoners after taking a case all the way to the Supreme Court to establish, in Rasul v Bush in June 2004, that, because the prisoners had no way of challenging the basis of their detention if they claimed to have been wrongly detained, they had habeas corpus rights; the right to challenge the basis of their imprisonment before a judge. The arrival of attorneys in the fall of 2004 finally punctured the veil of secrecy that had, to that date, enabled torture and abuse to take place with relative impunity.

However, despite the promise of the Rasul ruling, the struggle to secure meaningful rights for the prisoners was eventually derailed. First, Congress passed legislation intended to strip the prisoners of their newly granted habeas rights. It then took until June 2008, in Boumediene v. Bush, for the Supreme Court to issue a second habeas ruling, concluding that Congress had erred, and granting the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights.

That ruling led to a brief period in which the law actually applied at Guantánamo, and 38 prisoners had their habeas corpus petitions approved by judges, who impartially assessed the evidence, and concluded that the government had failed to make a case that they were involved with al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Along the way, the judges often exposed what objective research into the prison had firmly established — that the basis for rounding up prisoners and sending them to Guantánamo was horribly flawed, with no one actually caught "on the battlefield," as the U.S. alleged, and with the majority seized by the U.S.’s Afghan and Pakistani allies, at a time when the U.S. was offering substantial bounty payments (around $5,000 a head, a huge amount of money in Afghanistan and Pakistan) for anyone who could be packaged up as al-Qaeda or Taliban suspects.

Screening by the U.S. in Afghanistan, where all the prisoners were processed, was almost non-existent, so when the prisoners arrived at Guantánamo, very little was known about almost all of them, and when they then failed to respond to questioning about al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, because, in many cases, they had no information to provide, they were regarded as being terrorists trained to resist interrogation, and were then subjected to torture or other abuse designed to "break" them. This process, in turn, led to countless false statements being made, which fill the formerly classified military files that were released by WikiLeaks in 2011, for which I was a media partner.

Although there was a brief flowering of justice with regard to Guantánamo for a few years after the Boumediene ruling, politically motivated judges in the appeals court in Washington, D.C. responded by changing the rules and eventually gutting habeas corpus of all meaning for the Guantánamo prisoners by insisting that any information presented by the government had to be presumptively regarded as accurate.

Since 2010, no prisoner has been freed from Guantánamo as a result of a habeas corpus petition, and, with the law shut down yet again, prisoners have only been released at the whim of the president, or of Congress, and, in a few cases, through plea deals in the otherwise broken military commission trial system set up under the Bush administration to try prisoners at Guantánamo.

President Obama faced unprincipled opposition from Republican lawmakers over Guantánamo, but he responded by generally sitting on his hands, establishing himself as unwilling to spend political capital overcoming their opposition. He did, however, set up two review processes to assess the prisoners’ cases, which, although they had no legal power, ended up in 196 prisoners being released on his watch, compared to 532 under George W. Bush. Crucially, however, he left Guantánamo open for his successor to deal with as he saw fit.

41 men were still held at Guantánamo when Donald Trump took office, and Trump has shown no interest in releasing anyone, forcefully demonstrating how, fundamentally, Guantánamo remains a lawless place, where prisoners can only be freed if the president wants them freed. Although five of the 41 men he inherited from Obama were approved for release by the previous president’s review processes, and although only nine men are facing or have faced trials, Trump has, to date, released only one man, a Saudi sent back to ongoing imprisonment in Saudi Arabia, whose transfer out of the prison was only possible because of a plea deal he agreed in 2014.

With the doors of Guantánamo sealed shut by Donald Trump and a Republican majority in Congress, it would be enormously helpful if everyone concerned with justice and the rule of law joined us in saying to Donald Trump, on the 6,000th day of Guantánamo’s existence, "Not One Day More!"

FOR U.S. READERS: Please note that you can also encourage your Senators and Representatives to support our call to close the prison. Let them know that, while the prison remains open, it undermines America's values and national security. Find your Senators here, and your Representatives here.