Stop the Extradition: If Julian Assange is Guilty of Espionage, So Too are the New York Times, the Guardian and Numerous Other Media Outlets

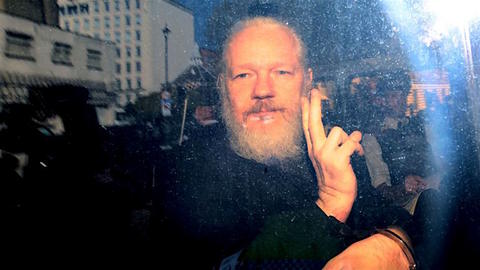

Julian Assange photographed after his arrest on April 11, 2019.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work in 2019. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, May 30, 2019

Nearly seven years ago, when WikiLeaks’ founder, Julian Assange, sought asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London (on June 19, 2012), he did so because of his "fears of political persecution," and "an eventual extradition to the United States," as Arturo Wallace, a South American correspondent for the BBC, explained when Ecuador granted him asylum two months later. Ricardo Patino, Ecuador’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, spoke of "retaliation that could endanger his safety, integrity and even his life," adding, "The evidence shows that if Mr. Assange is extradited to the United States, he wouldn't have a fair trial. It is not at all improbable he could be subjected to cruel and degrading treatment and sentenced to life imprisonment or even capital punishment."

Assange’s fears were in response to hysteria in the U.S. political establishment regarding the publication, in 2010 — with the New York Times, the Guardian and other newspapers — of war logs from the Afghan and Iraq wars, and a vast number of U.S. diplomatic cables from around the world, and, in 2011, of classified military files relating to Guantánamo, on which I worked as media partner, along with the Washington Post, McClatchy, the Daily Telegraph and others. All these documents were leaked to WikiLeaks by former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

Nearly seven years later, Assange’s fears have been justified, as, on May 23, the U.S. Justice Department charged him on 18 counts under the Espionage Act of 1917, charges that, as the Guardian described it in an editorial, could lead to "a cumulative sentence of 180 years."

The charges came six weeks after the Ecuadorian government — under new, pro-U.S. leadership — withdrew Assange’s asylum, leading to his immediate arrest by British police and his unacceptable imprisonment in Belmarsh, a maximum-security prison that is supposed to hold only dangerous convicted criminals, although it has also, since the "war on terror" began, been used to hold alleged terrorism suspects without charge or trial.

That same day, the U.S. began extradition proceedings, after unsealing a 2018 indictment against him "in connection with a federal charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion," as the Justice Department described it, relating to alleged efforts to assist Chelsea Manning to "crack an encoded portion of a passcode that would have enabled her to log on to a classified military network under a different user name than her own, which would have masked her tracks better," as the New York Times described it. Noticeably, Justice Department lawyers "have not alleged that his efforts succeeded," and in any case the charge only carries a maximum sentence of five years.

Clearly, though, that charge was just to pave the way for the indictment unveiled last week, which has, understandably, appalled defenders of free speech, enshrined in the U.S. in the First Amendment.

Among the many powerful rebukes to the Trump administration and the Justice Department, Glenn Greenwald’s column in the Washington Post two days ago, "The indictment of Assange is a blueprint for making journalists into felons," provides a commendable summary.

Greenwald notes that, although the U.S. government "has been eager to prosecute Assange since the 2010 leaks," up until now "officials had refrained because they concluded it was impossible to distinguish WikiLeaks’ actions from the typical business of mainstream media outlets."

"With these new charges," however, "the Trump administration is aggressively and explicitly seeking to obliterate the last reliable buffer protecting journalism in the United States from being criminalized, a step that no previous administration, no matter how hostile to journalistic freedom, was willing to take."

Dismissing dangerous claims that Assange "isn’t a journalist at all and thus deserves no free press protections," Greenwald also explains that "this claim overlooks the indictment’s real danger and, worse, displays a wholesale ignorance of the First Amendment." As he further explains:

Press freedoms belong to everyone, not to a select, privileged group of citizens called "journalists." Empowering prosecutors to decide who does or doesn’t deserve press protections would restrict "freedom of the press" to a small, cloistered priesthood of privileged citizens designated by the government as "journalists." The First Amendment was written to avoid precisely that danger.

Most critically, the U.S. government has now issued a legal document that formally declares that collaborating with government sources to receive and publish classified documents is no longer regarded by the Justice Department as journalism protected by the First Amendment but rather as the felony of espionage, one that can send reporters and their editors to prison for decades. It thus represents, by far, the greatest threat to press freedom in the Trump era, if not the past several decades.

If Assange can be declared guilty of espionage for working with sources to obtain and publish information deemed "classified" by the U.S. government, then there’s nothing to stop the criminalization of every other media outlet that routinely does the same — including the Washington Post, as well as the large media outlets that partnered with WikiLeaks and published much of the same material in 2010, along with newer digital media outlets like the Intercept, where I work.

As Greenwald also explains, "The vast bulk of activities cited by the indictment as criminal are exactly what major U.S. media outlets do on a daily basis," adding:

Outside the parameters of the Trump DOJ’s indictment of Assange, these activities are called "basic investigative journalism." Most major media outlets in the United States, including the Post, now vocally promote Secure Drop, a technical means modeled after the one pioneered by WikiLeaks to allow sources to pass on secret information for publication without detection. Last September, the New York Times published an article (titled "How to Tell Us a Secret") containing advice from its security experts on the best means for sources to communicate with and transmit information to the paper without detection, including which encrypted programs to use.

Many of the most consequential and celebrated press revelations of the past several decades — from the Pentagon Papers to the Snowden archive (which I worked on with the Guardian) to the disclosure of illegal War on Terror programs such as warrantless domestic NSA spying and CIA black sites — have relied upon the same methods that the Assange indictment seeks to criminalize: namely, working with sources to transmit illegally obtained documents for publication.

Stop the extradition

It cannot be said with any certainty that the charges against Assange will lead to a successful prosecution in the U.S., but the best way of making sure that it doesn’t happen would be for the British government to refuse to extradite him, which it is perfectly entitled to do; in fact, under the terms of the U.S.-U.K. Extradition Treaty, it is required not to agree to the request, because the treaty explicitly states that "[e]xtradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense."

Whether the British government will comply with this requirement is another matter. Holding him in Belmarsh seems to me to reveal the contempt with which they regard him, but even so it will be difficult for the British government to ignore what the Guardian described as the near-certainty that his "treatment in the American penal system would be more cruel than anything he might encounter even in our shameful prisons."

That said, Assange has clearly already been suffering in Belmarsh, as last night he was moved to the hospital wing of Belmarsh after what WikiLeaks’ website described as a "dramatic" loss of weight and deteriorating health, prompting "grave concerns" about his well-being.

"Mr Assange's health had already significantly deteriorated after seven years inside the Ecuadorian Embassy, under conditions that were incompatible with basic human rights," WikiLeaks said in a statement, adding, "During the seven weeks in Belmarsh his health has continued to deteriorate and he has dramatically lost weight. The decision of prison authorities to move him to the ward speaks for itself."

WikiLeaks also stated that, as the Evening Standard put it, "he could barely talk" when he met his lawyer, Per Samuelson, last Friday. Samuelson said that the state of his health was so poor that "it was not possible to conduct a normal conversation with him."

Noticeably, Chelsea Manning, who, unlike the Trump administration and the Justice Department, is fully aware of the difference between those who leak classified information for the public good, and those who publish it, and who is currently imprisoned for refusing to cooperate with a Grand Jury investigating Assange, after being imprisoned for seven years during the Obama presidency, released a statement from jail on the day Assange was charged with espionage in which she said she accepted "full and sole responsibility" for the 2010 WikiLeaks disclosures.

"It’s telling that the government appears to have already obtained this indictment before my contempt hearing last week," Manning said, adding, "This administration describes the press as the opposition party and an enemy of the people. Today, they use the law as a sword, and have shown their willingness to bring the full power of the state against the very institution intended to shield us from such excesses."

Today, former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger has joined the calls by high-ranking journalists and defenders of press freedom for Assange not to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act, which he described as "a panic measure enacted by Congress to clamp down on dissent or 'sedition' when the U.S. entered the First World War in 1917."

"Whatever Assange got up to in 2010-11," Rusbridger notes, "it was not espionage."

When Assange was first arrested by British police, I posted a link to the page on WikiLeaks’ website showing all the media partners it has worked with over the years. What is needed now is for everyone concerned with press freedom — with, in the U.S., the cherished First Amendment — to declare unconditionally that the charges are wrong, and that the U.K. should not extradite Assange to the U.S.

And while they’re at it, they might also want to point out that holding a journalist without charge or trial in Britain’s most notorious prisons for convicted criminals is not an act of justice, but one of vengeance.