The Broken Old Men of Guantánamo

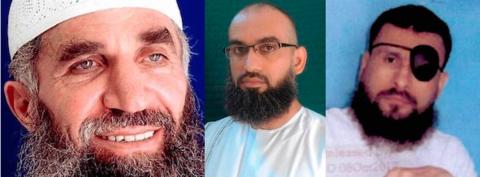

Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, Ammar al-Baluchi and Abu Zubaydah, three of the 14 men still held at Guantánamo who have not been approved for release.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work in 2023. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, May 21, 2023

In recent months, an often-submerged story at Guantánamo — of aging torture victims with increasingly complex medical requirements, trapped in a broken justice system, and of the U.S. government’s inability to care for them adequately — has surfaced though a number of reports that are finally shining a light on the darkest aspects of a malignant 21-year experiment that, throughout this whole time, has regularly trawled the darkest recesses of American depravity.

Over the years, those of us who have devoted our energies to getting the prison at Guantánamo Bay closed have tended to focus on getting prisoners never charged with a crime released, because, since the Bush years, when, largely without meeting much resistance, George W. Bush released two-thirds of the 779 men and boys rounded up so haphazardly in the years following the 9/11 attacks and the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, getting prisoners out of Guantánamo has increasingly resembled getting blood out of a stone.

Apart from a brief period from 2008 to 2010, when the law finally reached Guantánamo through habeas corpus (before cynical appeals court judges took it away again), getting out of Guantánamo has involved overcoming government inertia (for several years under Obama) or open hostility (under Trump), repeated administrative review processes characterized by extreme caution regarding prisoners never charged with a crime, and against whom the supposed evidence is, to say the least, flimsy (which led to over 60 men being accurately described by the media as "forever prisoners"), and many dozens of cases in which, when finally approved for release because of this fundamental lack of evidence, the men in question have had to wait (often for years) for new homes to be found for them in third countries.

This has been for a variety of reasons: because the entire U.S. establishment has refused to countenance sending them home to a country regarded as a security risk (in the case of Yemen), because it was regarded as unsafe to send them home (most notably in the cases of Guantánamo’s 22 Uyghurs), because they were effectively stateless (in the case of the prison’s handful of Palestinians, unable to return home because of Israel’s refusal to allow it), or because Republicans inserted provisions in the annual National Defense Authorization Act preventing their repatriation to number of other proscribed countries, including Afghanistan, Libya, Somalia and Sudan.

When Joe Biden became president, inheriting 40 prisoners from Donald Trump, the government finally recognized that it was unacceptable to keep holding "forever prisoners" indefinitely without charge or trial, and 19 of the 22 "forever prisoners" still held as of January 2021 have now been approved for release, although the typical inertia regarding Guantánamo, and a whole new raft of new resettlement problems raised by these men being finally approved for release means that most of them are still held.

However, the prison now holds just 30 men, and with 16 of these men approved for release — even though campaigners are still required to keep hammering away at the government to actually secure their release, on the unchanged basis that getting out of Guantánamo is still like getting blood out of a stone — there is now an opportunity, like never before, to focus on the 14 other men still held, who are mostly "high-value detainees," held and tortured in CIA "black sites," often for many years, before their arrival at Guantánamo between 2006 and 2008, and to raise uncomfortable questions for the U.S. government about what state they are in, physically and mentally, and what officials intend to do with them.

Six of these men were first charged in 2008 — five, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, in connection with the 9/11 attacks, and one other, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, in connection with the attack on the USS Cole in 2000. Successive governments — from Bush to Obama, and from Trump to Biden — have suggested that putting these men on trial demonstrates that something resembling justice exists at Guantánamo, but their cases have been stuck, for 15 years, in a "Groundhog Day" of seemingly endless pre-trial hearings, as their lawyers seek to expose the torture to which they were subjected, while prosecutors seek to keep it hidden.

In June 2013, a seventh prisoner, Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, another "high-value detainee" who arrived at Guantánamo in 2007, was also charged (and agreed to a plea deal last June), and in January 2021, just as Donald Trump left office, three other "high-value detainees" transferred to Guantánamo from "black sites" in September 2006 — Riduan Isamuddin (aka Hambali), an Indonesian, and two Malaysians, Modh Farik Bin Amin and Mohammed Bin Lep — were also charged.

Three of the other four men are "forever prisoners," including Abu Zubaydah, for whom the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program was first developed, in the mistaken belief that he was the number three in Al-Qaeda, and the fourth is Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, who is serving a life sentence, in solitary confinement, after a one-sided trial in which refused mount a defense in October 2008.

Obsessive secrecy

Guantánamo has always been defined by secrecy. Ostensibly, this has been for reasons of national security, but as time has passed it has become apparent that the secrecy is primarily a shield designed to prevent scrutiny of the vile treatment of the prisoners, and to prevent any accountability.

It took nearly two and a half years from when the prison opened, on January 11, 2002, for lawyers to secure a Supreme Court victory, in Rasul v. Bush, in June 2004, that allowed them finally begin representing men held at Guantánamo, and even then every word of the hand-written notes that they took of their meetings with their clients was presumptively classified. The lawyers had to hand in their notes after every meeting, and had to travel to a secure Pentagon facility in Virginia to see them, and to learn whether any of the content had been subsequently unclassified by a Pentagon review team.

In the cases of the mass of ordinary prisoners at Guantánamo — soldiers mislabelled as terrorists, civilians swept up by mistake —some these notes were subsequently unclassified, and some of the information in them eventually made its way to the mainstream media, helping to reveal aspects of Guantánamo’s hidden truths.

From the beginning, however, every word uttered between lawyers and the "high-value detainees" remained classified, largely preventing the outside world from knowing anything about them.

While some information leaked out during the interminable pre-trial hearings, via the tenacity of some of the prisoners’ lawyers (and an ICRC report, based on interviews with the "high-value detainees" after their arrival at the prison in September 2006, caused ripples of shock when it was leaked in 2009), it wasn’t until the publication, in December 2014, of the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s extraordinary report about the CIA’s torture program that some particular horrors became public knowledge; in particular, that, in the "black sites," amongst all the death threats, forced nudity, sleep deprivation, physical violence and waterboarding, interrogators also conducted rectal exams with "excessive force," and some of the prisoners were anally raped with food, their meals puréed and inserted into their rectums.

As the Guardian described it at the time, "Prisoners were subjected to 'rectal feeding' without medical necessity," and one prisoner, Mustafa al-Hawsawi, one of the five men charged with involvement in the 9/11 attacks, was "later diagnosed with anal fissures, chronic hemorrhoids and 'symptomatic rectal prolapse.'" In 2016, when al-Hawsawi’s medical situation was so severe that rectal surgery was required, his defense attorney, Walter Ruiz, told reporters that al-Hawsawi "was tortured in the black sites. He was sodomized." Ruiz advised them to "shy away from terms like rectal penetration or rectal rehydration because the reality is it was sodomy," adding that, as a result of this torture, he had "to manually reinsert parts of his anal cavity" to defecate.

Making matters worse, Guantánamo was not adequately equipped to deal with any kind of complicated surgery. If personnel on the base faced any kind of medically complicated complaint, they were flown to the mainland for treatment, but for the prisoners that was not possible —and is still not possible to this day. Since 2010, a provision in the annual National Defense Authorization Act, inserted by Republican lawmakers every year, prevents any Guantánamo prisoner from being sent to the U.S. mainland for any reason, including for urgent medical treatment that is unavailable on the naval base.

The progressive and alarming physical deterioration of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi

Despite these gruesome revelations, however, it has taken many more years for the ban on prisoners receiving medical treatment on the U.S. mainland to result in international condemnation, even though it has been apparent since 2017 that Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, who has a degenerative spinal condition, and is the most physically disabled of Guantánamo’s ill and aging prisoners, faces paralysis because of the ban.

Although he "was diagnosed with spinal stenosis in September 2010," as the Center for Victims of Torture has explained, al-Iraqi (whose real name is Nashwan al-Tamir, and who is 61 or 62 years old) "did not receive surgical treatment until his condition became severe seven years later, when he 'began to experience a significant loss of sensation in both of his feet and a loss of bladder control.'" He subsequently "received four additional surgeries performed at Guantánamo by off-island specialists," because of the ban, but is still suffering, and may require additional surgery.

Last June, al-Iraqi, who appears to have been a military commander rather than anyone involved with terrorism, agreed to a plea deal, which I reported here, and which, I think it is fair to say, was undoubtedly offered by the U.S. authorities because they don’t want the negative PR of another prisoner dying at Guantánamo, or ending up completely paralyzed. Under the terms of the plea deal, he will be eligible for release in June next year, providing time for the U.S. government "to find a sympathetic nation to receive him and provide him with lifelong medical care," as Carol Rosenberg explained for the New York Times, as well as holding him while he serves out the rest of whatever sentence is decided by his military jury, although whether a suitable country can be found is another matter.

In January this year, a number of U.N. human rights experts, including Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, finally condemned the U.S. government for its treatment of al-Iraqi, in an 18-page report that was submitted on January 11 (the 21st anniversary the opening of Guantánamo), after al-Iraqi had undergone a seventh surgery, but which was not made public until the end of March.

In the report, the experts expressed their concern "regarding the deteriorating health situation of Mr. al-Tamir stemming from the alleged lack of available, accessible and adequate healthcare services, treatment, diagnostics, and reasonable accommodations required because of his disability, mental and physical trauma, older age, religion, and nationality, among others," and also expressed concern about his mental health, about the "Use of Force and Degrading Treatment," and "the potential negative impacts of his health condition on his access to justice and right to a full defense."

Fionnuala Ní Aoláin subsequently visited Guantánamo, in what was the first ever visit by a U.N. expert, because all previous attempts had either been thwarted "by the hostility of the U.S. government, or through a failure on the part of officials to guarantee that any meetings that took place with prisoners would not be monitored," as I explained in an article in February, and her report, when issued, will no doubt contribute significantly to increased pressure on the Biden administration to free everyone who has not been charged, and to find an acceptable and humane solution to the cases of those caught up in the inadequate military commission trial system.

The hidden truth about Ammar al-Baluchi’s CIA-inflicted brain damage

Al-Iraqi’s case is not the only one that has surfaced from Guantánamo’s entrenched secrecy to shame the U.S. government. Last March, just before his plea deal was announced, some of those tenacious lawyers I mentioned above — the legal team for Ammar al-Baluchi, one of the five men charged with involvement in the 9/11 attacks — secured access to a 2018 report by the CIA Inspector General, which was previously hidden from them, and in which, as the Guardian described the report’s conclusions, al-Baluchi was, while naked, "used as a living prop to teach trainee interrogators, who lined up to take turns at knocking his head against a plywood wall, leaving him with brain damage."

The extent of that brain damage was revealed when a neuropsychologist "carried out an MRI of Baluchi’s head in late 2018," as the Guardian described it, and "found 'abnormalities indicating moderate to severe brain damage' in parts of his brain, affecting memory formation and retrieval as well as behavioral regulation." The specialist also found that the "abnormalities observed were consistent with traumatic brain injury."

In January this year, further problems with al-Baluchi's health were discovered when an MRI scan revealed that he has a small tumor located on his spine. As Middle East Eye explained, independent medical experts said that it was "likely spinal meningioma," which is usually benign, but that it will "eventually affect motor or sensory nerves as it grows" — highlighting, yet again, the challenging medical environment at Guantánamo, as ever-increasing medical problems surface.

Al-Baluchi’s defense team is led by James Connell and Alka Pradhan, who I have known for many years, and in March, when I met with Connell as he was visiting London, I came up with the title for this article during a discussion about the plight of Guantánamo’s aging prisoners, the failure of the U.S. authorities to provide them with adequate treatment, and another little-known fact — that many of these men appear older than they are. Back in 2014, when Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi was arraigned, Carol Rosenberg reported that he "looked significantly older than his pre-capture photo," and when Connell described al-Baluchi to me as appearing to be an old man, physically and mentally, he added swiftly that he is only 45 years old.

Last month, Patrick Hamilton, the International Committee of the Red Cross’s head of delegation for the United States and Canada, visited Guantánamo, during one of ICRC’s regular visits, for the first time since 2003, when he was a Pashtu interpreter early in his career, and noted, in a rare public statement from the ICRC, "I was particularly struck by how those who are still detained today are experiencing the symptoms of accelerated ageing, worsened by the cumulative effects of their experiences and years spent in detention," adding that "[t]heir physical and mental health needs are growing and becoming increasingly challenging."

Hamilton also noted that, "While the current authorities are offering some temporary solutions, there is a need for a more comprehensive approach if the U.S. is to continue holding detainees over the years to come," and, as he proceeded to explain, "All detainees must receive access to adequate health care that accounts for both deteriorating mental and physical conditions — whether at Naval Station Guantánamo Bay or elsewhere. This includes cases of medical emergencies. At the same time, consideration must be given to adapting the infrastructure for the detainees’ evolving needs and disabilities, as well as the rules that govern their daily lives."

Plea deals

The ICRC’s observations and suggestions will, of course, add to the pressure on President Biden to resolve the issues relating to the care of aging prisoners that, until his administration took office, had been largely or entirely ignored, although, as the U.S. author Moustafa Bayoumi noted in a major profile of Ammar al-Baluchi published in the Guardian last week, one step towards this was taken in March 2022, when prosecutors in the military commissions, reeling from a devastating account of torture which was delivered by Majid Khan, a remorseful former Al-Qaeda courier, at his sentencing in October 2021, and which had led seven of the eight officers on his military jury to recommend clemency, finally recognized that their long-cherished dream of successfully prosecuting and executing KSM and his four alleged accomplices was untenable, and that plea deals were the only way forward.

As Moustafa Bayoumi explained, "In March 2022, the government approached defense teams in the 9/11 trial for plea negotiations. While details haven’t been made public, the broad outlines have been reported. The men would plead guilty and the government, in exchange, would no longer seek the death penalty. Since Congress passed a law forbidding the transfer of any Guantánamo detainee to the U.S. mainland, sentences would probably be served at Guantánamo Bay. The length of sentence would be worked out individually for each of the five."

Bayoumi also explained that policymakers would also have to be involved in making decisions about the very specific "conditions of confinement, rehabilitation from torture, and adequate medical care" that would also be required for plea deals to be successfully negotiated, although, 14 months on, nothing has been heard from Caroline Krass, the general counsel of the Department of Defense, who would have to agree to the proposals, and who, "perhaps problematically," as Bayoumi put it, "also served as general counsel for the CIA between 2014 and 2017."

Despite the delay, I don’t see how the solutions outlined above, which would also have the support of the U.N. and the ICRC, can ultimately be avoided, with plea deals also extended to Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, and Hambali and his two alleged accomplices, and with Ali Hamza al-Bahlul finally relieved of the solitary confinement to which has been subjected for the last 14 and a half years, not by design, as such, as I explained in an article last December, but because the general collapse of the military commissions meant that the other prisoners who were supposed to share his cell block never materialized.

The remaining "forever prisoners"

In addition, plans for a facility that can provide "rehabilitation from torture, and adequate medical care," but without being a prison, might be the only practical solution for other men still held for whom release seems improbable — including some, or all of the three remaining "forever prisoners."

Of the three, by far the best-known is Abu Zubaydah, the torture program’s first victim, held for four and a half years in CIA "black sites" before his transfer to Guantánamo in September 2006 with 13 other "high-value detainees." In forensic detail, Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy pieced together the almost unbearable story of his torture for a book published last year, "The Forever Prisoner," and a documentary of the same name was also made by Alex Gibney.

More recently, as I reported in detail last month, in an article entitled, "U.N. Condemns 21-Year Imprisonment of Abu Zubaydah as Arbitrary Detention and Suggests that Guantánamo’s Detention System 'May Constitute Crimes Against Humanity'", the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded that his 21-year imprisonment constitutes arbitrary detention, and demanded his release, and compensation for his life-shattering ordeal, and just last week there was renewed outrage about his treatment, and the whole of the post-9/11 torture program, when the Center for Policy and Research at Seton Hall University Law School in the U.S., whose director is one of his attorneys, Mark Denbeaux, released a new report about his torture, illustrated with his own drawings, which was published in the Guardian and picked up around the world.

However, while I don’t doubt that the Biden administration will have been shaken by the U.N.’s report in particular, which I described as "the single most devastating condemnation by an international body that has ever been issued with regard to the U.S.’s detention policies in the 'war on terror,' both in CIA 'black sites' and at Guantánamo," freeing him — even if a decision to approve his release is finally forthcoming, after his most recent PRB in July 2021, which failed to reach a decision — is no easy matter.

Although he grew up in Saudi Arabia, Abu Zubaydah does not have Saudi citizenship, because his parents were Palestinian, and, as a result, he is effectively stateless. And while there is a strong humanitarian argument for a third country to offer him a new home, it is, to be frank, difficult to imagine any country stepping up to help out without the U.S. embarking on the kind of charm offensive — involving untold benefits for the host country— that recently took place to secure the resettlement of Majid Khan in Belize, and which, in Abu Zubaydah’s case, would also require the U.S. government to very publicly repudiate all the mistaken claims it made over the years about his involvement with Al-Qaeda, potentially opening the floodgates for unlawful imprisonment claims that they no doubt want to keep at bay forever, if possible.

I suspect that similar problems also face the other two "forever prisoners" — Abu Faraj al-Libi, another "high-value detainee" brought to Guantánamo in September 2006, and Muhammad Rahim, an Afghan, also regarded as a "high-value detainee," who was the last prisoner to arrive at Guantánamo, in March 2008.

Al-Libi, who also suffers from problems relating to his torture, had his ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial approved by a PRB last August, on the continuing basis of his alleged involvement with Al-Qaeda, while Rahim, also accused of involvement with Al-Qaeda, had his ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial upheld last April. Even if both men secure a recommendation for release at their next PRBs, however, neither can be repatriated, and, as with Abu Zubaydah, it is difficult to imagine a third country volunteering to offer them a new home without extraordinarily high-level intervention at the highest levels of government.

In addition, out of the 16 men still held who have been approved for release but are still held, two — a Tunisian and a Rohingya Muslim who reportedly has Pakistani citizenship — are also particularly problematical for the authorities because, although they were approved for release over 13 years ago, they have persistently refused to engage with the authorities regarding their release. I also suspect that one or two others may have problems being resettled, either because of health conditions that require significant support on the part of a host country, or because of terrorist associations that still cling to them despite being unanimously approved for release by high-level government review processes.

Practically, then, to conclude this review of the obstacles still standing in the way of Guantánamo’s closure, the most realistic conclusion is that two state-of-the-art facilities — one a prison, the other not — will have to be built, able to provide "rehabilitation from torture, and adequate medical care" for as long as the men in question — perhaps half of the 30 men still held — remain alive.

The cost, once the insanely expensive military commissions are abandoned, will be a fraction of the half a billion dollars a year that it currently costs to operate the prison, but it is the bare minimum that the U.S. government can —and should — provide as the price of its responsibility for tearing up all domestic and international laws and treaties regarding prisoners and their treatment after 9/11.