Held for 700 Days Since Being Approved for Release: Hassan Bin Attash, Guantánamo’s Youngest Prisoner

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, March 18, 2024

Last Wednesday (March 13) marked 700 days since Hassan Bin Attash, a Saudi-born Yemeni, was unanimously approved for release from Guantánamo by a Periodic Review Board, a high-level U.S. government review process, and this article, telling his story, is the eighth in an ongoing series of ten articles telling the stories of the 16 men (out of 30 still held in total) who have long been approved for release. The articles are published alternately here and on my own website, with their publication tied into significant dates in their long ordeal.

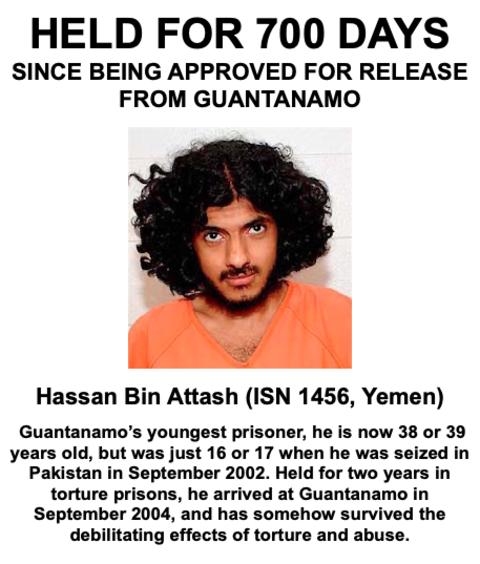

Guantánamo’s youngest prisoner, Hassan is 38 or 39 years old, and has been held without charge or trial for well over half his life. Seized in a house raid in Karachi, Pakistan on September 11, 2002, he was just 16 or 17 years old at the time. The photo above, included in his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in 2011, shows him as he was in 2008 at the latest, but no more up to date photo of him exists.

As a juvenile, Hassan was supposed to have been rehabilitated rather than punished, according to the Optional Protocol to the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, which the U.S. government signed just four months after his capture, but unfortunately, when it came to respecting his rights, he was triply unfortunate.

Firstly, the Bush administration didn’t care that children or juveniles seized in the "war on terror" were not responsible for their actions, for which accountability lay with those directing them (their parents or siblings, or some other authority figure). In Hassan’s case, his further misfortunes stemmed from the fact that he was seized with Ramzi bin al-Shibh, a Yemeni regarded as a significant accomplice in the 9/11 attacks, and the fact that his elder brother was Walid bin Attash, another individual regarded as having played a major role in 9/11.

After his capture, Hassan was tortured for two years before finally arriving at Guantánamo in September 2004. After a few days of torture in a Pakistani prison (with U.S. operatives present), and a few more days in the "Dark Prison," a CIA "black site" in Afghanistan, where prisoners held and tortured in medieval squalor were additionally bombarded by screamingly loud music for 24 hours a day, he was flown to Jordan, to a proxy torture site run by Jordan’s notorious intelligence service, the General Intelligence Directorate (GID), where he was tortured for 16 months on behalf of the CIA. In January 2004, he was returned to the "Dark Prison" for four months, and was then transferred to the U.S. prison at Bagram airbase for another four months of torture before his eventual transfer to Guantánamo, where he has been held ever since without charge or trial.

Mansoor Adayfi’s recollections of Hassan bin Attash

Four years ago, former prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, the author of a compelling memoir, "Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo," (published in 2021) sent me a profile of Hassan, which I intended to publish, although that plan was derailed because its arrival in my inbox coincided with the first Covid lockdown, which rather came to dominate every other topic.

However, to mark Hassan’s shameful ongoing imprisonment, nearly two years since he was approved for release, I’m including parts of Mansoor’s article in this profile, which I hope will be of interest.

As Mansoor explained, "The first time I met Hassan was at the end of 2005 when we went on a massive hunger strike. Hassan participated in the hunger strike, trying to escape the torture at Camp 5 [the block used for "non-compliant" prisoners, and/or those regarded as significant]. I saw a young, lost, unstable boy who seemed to struggle to survive and had difficulty communicating. We thought he was crazy. He talked to no one, would suddenly laugh, and had nightmares, forgetfulness, and frequent panics of fear from time to time that unconsciously drove him to tear out his hair."

Hassan’s behavior at this time can very clearly be identified as involving severe mental health issues relating to his torture, and yet the U.S. authorities did nothing to help him. Instead, as Mansoor explained, it was "obvious that Hassan and some detainees were being targeted, and there was a special program designed for them."

As he proceeded to explain, "Hassan participated in each protest to try to stop the torture, to meet his brother, and to get medical attention and treatment, but the guards never left him alone, provoking and punishing him instead. In Camp 5, they never let him sleep. Each shift would knock on his door every seven to ten minutes. We fought with the guards to stop it, but they would say, 'We can’t, we have orders.' Hassan lost weight, his hair started falling out, and large black circles appeared around his eyes. We started fighting with the guards to stop. Hassan had no choice but to try to push back, but that was what the interrogators wanted; they wanted to drive him crazy and to break him over and over again."

According to Mansoor, Hassan spent three years on a hunger strike, being force fed, and he didn’t meet him again until, eventually, in 2012, he was moved to Camp 6, where the prisoners were allowed to spend time together communally.

When he asked Hassan to tell him his story in his own words, he said, "Like many Arabs, I was sold by the Pakistani government to the CIA. I was only sixteen years old. I had no interest in either Al-Qaeda or Jihad. My elder brother took me with him to Afghanistan, I fled to Pakistan and lived there, spending my time playing games at the games club and learning how to cook in a restaurant. The first CIA question was about my brother, from whom I had fled. I told them I had no idea about him, and in fact I didn’t want him to find me. I didn’t know what they were after. They threatened to take me to Egypt, Israel or Morocco. I got some slaps and beatings in Pakistan. I cried. I didn’t know that worse was yet to come."

As Hassan proceeded to explain, "The CIA shipped me to Jordan. I spent around 16 months under interrogation for 12 to 20 hours a day. Hanging, slapping. They would force me to lie down, strip me naked, and they would step on my body and face. There was no sleep. They would drag me back and forth to the interrogation room. They would secure my feet on a board and would beat the soles of my feet until they became raw. Then they forced me to stand on half-melted salt. It was like walking on hot coal. The CIA agents were there giving the instructions. A young Jordanian soldier would always apologize to me, saying, 'When I look at you, I see my young brother, who is your age. Please, forgive me. I can’t sleep at night, your cries and screams haunt me. They are after your brother. I’m sorry, I wanted to let you know.'"

Hassan added, "The worst thing I experienced there was the sleep deprivation. They tortured me mercilessly, and they told me that no one knew I was in Jordan so if they killed me nobody would know. I begged them to stop. They were after my brother, they told me that over and over again. They forced me to sign a lot of papers that I have no idea what they were about. I was crying, I didn’t know what else to do."

As he also explained, "One day they came to me telling me that I was going home. I was so happy. I was dragged to an airplane, but I didn’t mind being dragged as long as I was going home. To be honest, I had no choice; I was at their mercy. The treatment on the plane was neither first-class nor business class, it was the CIA class, a special airplane with a special service of loud music, punches to the face and kicking. I was like a toy in their hands. The plane landed, and then again I was dragged to the CIA 'black site,' the 'Salt Pit' [aka the 'Dark Prison'], where another journey of torture began. I wished I would be sent back to the Jordanian torturers. The CIA never stopped, no matter how close I was to death. 'We have no interest in you. We need you to help us to get your brother,' they kept telling me over and over again."

In fact, Hassan’s brother Walid was seized in Pakistan seven months after Hassan, in April 2003, and had been in CIA "black sites" ever since, but it seemed to make no difference to Hassan’s torturers. Eventually, in Guantánamo, after his brother was brought there in September 2006, the authorities’ approach changed, as Mansoor also explained, citing FBI agents interrogating both Hassan and Walid, telling Hassan, "We have no interest in you. Your only way out of Guantánamo is to be a witness in court against your brother," and telling Walid, "Your brother’s freedom is in your hands. The sooner you cooperate and accept our deal the earlier your young brother can leave Guantánamo."

Somehow, despite Hassan’s immense suffering, he seemed to recover somewhat in Camp 6, where, as Mansoor explained, he "spent most of his time in a kitchen or playing PS3," adding, "You could hear his voice and his laughter from a mile away. When we heard him, we knew that he had won the game. I don’t think any of you would have a chance of winning if you played against him."

As Mansoor also explained, "When it comes to cooking, he is one of the best chefs we had at Guantánamo. Hassan cooked for detainees and guards; he had many friends who were guards and who liked his food."

Mansoor also spoke to a former prisoner, Omar, who had known Hassan since he was 14 years old. When he asked him, "Did you know Hassan in Afghanistan?," Omar said, "Oh, that poor kid. I remember when his older brother brought him to Afghanistan. He was only 14 years old. He didn’t like living there, and he escaped to Pakistan, where he spent his time playing games at the electronics store or in a restaurant where he cooked. He loved food more than anything and eats like a horse. You saw him at Guantánamo with games and food. The U.S. government keeps him at Guantánamo to pressure his brother."

Despite everything, Hassan has in many ways overcome adversity with extraordinary tenacity, becoming fluent in English, and seeking to enrol on a college course to study the English language (although that request was denied by the prison authorities). Perhaps the secret to his survival is because, as Mansoor suggested, "One thing that distinguishes Hassan is that he holds no grudge towards anyone. He still lives in his teens; he might grow up physically, but mentally he is still as a teen."

He added, "What I like best about him is his generosity and the innocence of his soul, although sometimes he would drive me crazy. When I would ask him about the CIA and Jordanian interrogators, he would answer, like a boy, 'They are crazy. They don’t know what they want.' When I would look at Hassan's face, it would show no hate or grudge, just a boy's reaction."

The Periodic Review Boards

After Hassan’s long ordeal during the Bush administration, involving, initially, his torture to reveal the whereabouts of his brother, and, later on, his torture to persuade him to testify against him instead, his case was finally reviewed, in 2009, by a high-level interagency review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which reviewed the cases of the 240 prisoners inherited by President Obama from his predecessor. Sadly, although the task force recommended 156 prisoners for release, Hassan was not one of them. Instead, he was one of the 36 men recommended for prosecution, although that never happened.

Over the following years, Obama administration officials shunted most of those recommended for prosecution into a second review process, the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), initially conceived to review the cases of 48 men recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by the task force, on the dubious basis that they were "too dangerous to release," even though the task force members conceded that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

By the time the PRB process belatedly began, in November 2013, it applied to 64 prisoners in total, and Hassan was the last to have his case considered, in September 2016. Cynically, I believe, the U.S. authorities now claimed that he was born in 1982, and not 1985, meaning that he was not a juvenile when seized, and also paraded a series of absurd allegations about him — that he pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden in 1997, when he would have been 12 years old, and that he "was skilled in bombmaking and contributed to al-Qa’ida’s explosives activities and capabilities," despite the accounts, from Hassan himself, and from those who knew him, that all he was interested in was cooking and playing computer games.

The authorities also noted that, "until 2013, [he] was non-compliant and hostile with the guard staff," but recognized that, "[i]n August 2013, he became highly compliant," although they claimed that "he continues to harbor an extremist mindset," even though his attorney, David Remes, specifically noted that he had "never heard him deprecate the American people or American values, or express extremist views." Remes also described him as "engaging," and with "a quick wit," ad as someone who "reads people well," and has developed "a strong sense of right and wrong." He also priased his English language skills, and his "insatiable appetite for news about current events," and noted that he "found him to be more sensible and level-headed than many others his age."

Despite this, his ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial was upheld the following month, with the board members evidently concerned about his alleged past activities and his mindset. His next review took place under Donald Trump, but by that time the majority of the prisoners — Hassan included — boycotted their hearings, having correctly concluded that it had become a sham process, and it was not until January 2022 that he finally had another opportunity to persuade a PRB to approve him for release.

The time around, over five years since he attended his last hearing, and over eight years since his compliant behavior had been noted by the authorities, Hassan, now 36 or 37 years old, was again identified as not posing a threat to the U.S. by his attorneys, George Clarke and Cameron Reilly, who had taken over his representation in 2018, and who noted, as David Remes had, that they had "never heard Hassan deprecate the American people or American values, or express extremist views."

After also noting his English language skills, his cooking skills and his enthusiasm for learning, the attorneys added that, for several years, he had been "a block leader," who was "responsible for solving daily routine issues between other detainees and the guards," and also pledged to support him after his resettlement.

Their endorsement of Hassan’s qualities was echoed by his Personal Representative (a military official assigned to represent him), who stated that "the influence that nearly two decades of being surrounded by American culture has had on him is apparent," adding that, "In addition to speaking English fluently, he is comfortable with people of different backgrounds and beliefs," and also explaining that his fluency in English is so pronounced that "he hopes to eventually gain employment as a translator," and "has been working towards this goal."

The Representative added that "Hassan’s outlook on life is remarkably positive," and that he "believes that his capture and subsequent detention changed the trajectory of his life," also explaining that he "has used his time at Guantánamo to read and learn about world history and religion," and that he "candidly discussed with me how his understanding of the world has changed as he has become more educated and informed."

Approved for release but still not freed

Hassan was finally approved for release on April 13, 2022, but as George Clarke pointed out to me in an email at the time, although he and Cameron Reilly were "grateful to the board for clearing Hassan, unless the administration starts to take repatriation of all of the cleared detainees seriously, it will be a meaningless act."

700 days later, those words really ought to be taken seriously by the Biden administration, but as I’ve been obliged to explain throughout this series of articles, Hassan and the 15 other men unanimously approved for release are the victims of a lamentable and inexcusable inertia at the very top of the U.S. government — in the White House, and in the offices of Antony Blinken, the Secretary of State.

This is because the decisions taken to release Hassan and the other men were purely administrative, and no legal mechanism exists to compel the government to actually free them, if, as is increasingly apparent with every passing day, President Biden and Secretary Blinken cannot be bothered to prioritize their release.

This is in spite of the fact that it is reasonable to assume that Tina Kaidanow, a former ambassador appointed as the Special Representative for Guantánamo Affairs in August 2022, who is "[r]esponsible for all matters pertaining to the transfer of detainees from the Guantánamo Bay facility to third countries," has located a viable country that is prepared to offer new homes to at least some of these men.

As has so often been the case throughout Guantánamo’s long and sordid history, it seems apparent that these men’s long-awaited and long-deserved freedom is being sacrificed for political expediency of the basest kind; namely, the administration’s desire to keep Republicans onside, to support a seemingly bottomless supply of weapons to Ukraine and Israel, which might be threatened — by a handful of extreme, Guantánamo-loving Republican Senators — if any of these men were to be freed, to resume their long-suspended lives.

As well as being a graveyard of international humanitarian law, it seems that Israel’s assault on Gaza is also, as a by-product, ensuring that men approved for release are not being freed from Guantánamo. This is a lamentable situation that, I can only hope, is being regarded by the men in question as yet another test of their endurance, which has, shamefully, been tested for far longer than most western commentators can even imagine.