The Ongoing Horrors of Guantánamo: Men Held “Not Because They Did Anything Wrong, But Because It’s Not Politically Advantageous to Care About Them”

Campaigners call for the closure of Guantánamo on January 11, 2024. Clockwise, from top L: New York, Washington, D.C., Mexico City and London.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, June 12, 2024

For those of us who were alive in 2001, and old enough to appreciate what happened on September 11, 2001, and the U.S. government’s response — in particular when, four months later, the "war on terror" prison at Guantánamo Bay first opened — it’s been a long and often gruelling effort to get people, first of all, to recognize that one atrocity (9/11) doesn’t justify another (the multiple atrocities, in fact, of the illegal invasion of Iraq, the lawless U.S. prisons in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the horrors of Guantánamo and the CIA "black site" torture prisons), and then to get them to even be aware that the last surviving bastion of the "war on terror" — Guantánamo — is still open, let alone that 30 men are still held there, mostly as deprived of fundamental rights as they were when the prison first opened nearly 22 and a half years ago.

From open hostility in those early years, when a dangerous Islamophobia stalked the land, to a glimmer of awareness that Guantánamo might have been a mistake (at the time of the 2008 Presidential Election), the last 15 years have largely consisted of amnesia when it comes to Guantánamo.

Many Americans believe that, when President Obama promised to close Guantánamo in January 2009, this meant that he had actually followed up on his promise, when the reality, as those of us who continued paying attention are all too aware, is that his promise floundered, partly in response to unprincipled Republican opposition, and partly through a specific failure, on Obama’s part, to expend political capital on dealing with a grievous moral scar that had no obvious electoral upside.

Today, I fear, most Americans alive at the time of 9/11 never even think about Guantánamo, while those who are younger, as well as not even knowing what Guantánamo is, may also not even know about the 9/11 attacks. Although strenuous efforts were made over many years to maintain the anniversary of 9/11 as a day of national mourning, and to keep fanning the flames of vengeance that had fired up the "war on terror," the calamity of that day has receded into the past, as has the Bush administration’s extraordinarily violent response to it.

I’ve been thinking about all of the above since reading an excellent article, "Guantánamo Bay Has Shattered the Illusion of a 'Fair' Justice System," written for the Current Affairs website by Stephen Prager, a 25-year old journalism graduate, born in 1999, who was too young to appreciate what happened on 9/11, and in the subsequent "war on terror," but who has managed to free himself from the miasma of amnesia to which institutionalized apathy — including the failures of the mainstream media to consistently recognize Guantánamo’s significance — was supposed to have consigned him.

I’m posting Prager’s article below, in which he credits the artist and writer Molly Crabapple with first having alerted him to the injustices of Guantánamo when he was 14 years old, and brings the story of Guantánamo up to date by picking up on the recently revealed story that, of the 16 men still held (out of 30 in total) who have long been approved for release, eleven of them were supposed to have been resettled in Oman in October, but had their flight cancelled at the last minute because of "political optics" following the attacks on Israel by Hamas and other militants on October 7.

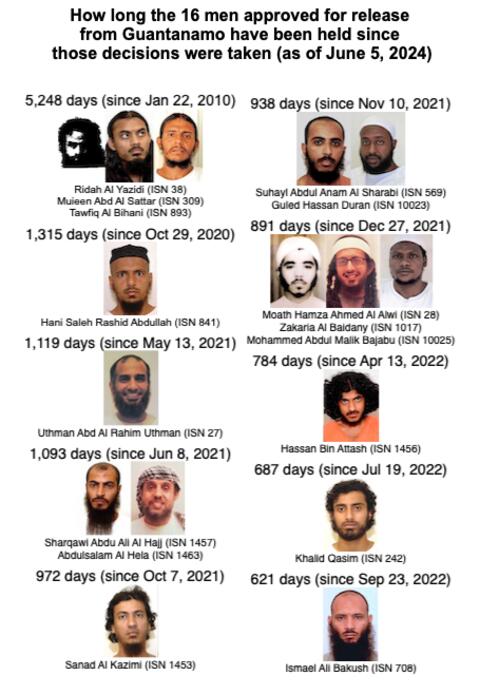

Prager also, I’m pleased to note, picks up on the posters I’ve been preparing, every month since the most recent prisoner release last April, showing how long these 16 men have been held since the decisions to release them were taken, a scandal that, as so often with the mainstream media, no one has taken any interest in whatsoever.

Guantánamo Bay Has Shattered the Illusion of a 'Fair' Justice System

By Stephen Prager, Current Affairs, June 5, 2024

Guantánamo stands out as one of the most extreme examples of how people’s lives can be totally ruined not because they actually did anything wrong, but because it was simply not politically advantageous for anyone to care what happened to them.

When you grow up in America, one of the ideas drilled into you from birth is that you were born in a "free" country. As a person born in 1999, I first conceived of myself as an "American" right at the frothing heights of the War on Terror. As a young child, I was particularly obsessed with maps and flags for some reason. One of the first things I internalized about the world was that there were "free" nations and "unfree" nations and that I was fortunate enough to have been born into one of the free ones. That idea was particularly salient at the time, when the notion of a civilizational clash against enemies who "hate our freedom" was central to the Bush administration’s case for war in the Middle East.

I couldn’t understand the post-9/11 discourse at the age of 4, of course. But because of endless repetition of the phrase "free country" by family, teachers, and television, the idea got wedged into the deepest recesses of my mind. As I got older — and was repeatedly taught the Founding Fathers’ idealism and struggle against tyranny — that idea came to be associated with expectations like freedom of the press, freedom of religion, and a judicial system that supposedly treated everyone — regardless of wealth or background — fairly.

I bring all this up because the first time I can recall when my faith in this world order began to fracture was when, as a young teenager with only a dim knowledge of politics, I learned about the existence of the U.S.-run prison camp at Guantánamo Bay. I had always been vaguely aware that a place with that name existed, but up until that point in my life, I’d never been taught about it in any of my classes. (I’m pretty sure that until about my freshman year of high school, if you’d asked me what Guantánamo Bay was, I’d have probably said it was a vacation spot like Jamaica’s Montego Bay.)

My first real encounter with the reality of Guantánamo was the fantastic 2013 VICE feature "It Don’t Gitmo Better Than This" by Molly Crabapple (the title references a T-shirt you can buy in the prison’s gift shop). I’m not sure what exactly possessed me to read the article, but it surely had something to do with the haunting, Steadman-esque illustrations (also by Crabapple) which depict faceless U.S. military personnel lounging in absent-minded revelry as an inmate is restrained and force-fed in the background.

Molly Crabapple's alarming and surreal illustration of guards at Guantánamo, accompanying her 2013 VICE article.

Since the prison opened in 2002, Crabapple had been one of a select few journalists given clearance to visit the secretive camp. At the time, she wrote:

Gitmo's prison camps were built, in principle, to hold and interrogate captives outside the reach of U.S. law. Nearly 800 Muslim men have been imprisoned since it opened, and the vast majority of them have never been charged with any crime. Since he was inaugurated in 2008, President Obama has twice promised to close Gitmo, but 166 men still languish in indefinite detention. It is a place where information is contraband, force-feeding is considered humane care, staples are weapons, and the law is rewritten wantonly.

Much of the article focuses on one inmate, 34-year-old Nabil Hadjarab, who, at the time of writing, had been languishing in Gitmo for more than 11 years. Though he’d been approved for release since 2007, he was continuously detained for more than six years afterward. He was one of 106 inmates who’d gone on a hunger strike in protest of their indefinite detention. As with dozens of other inmates, he’d grown so thin that the guards had taken to forcibly feeding him through a tube to keep him alive.

Crabapple was not allowed to speak with Hadjarab directly, but she spoke with his attorney and reviewed documents about detainees that had been released by whistleblower Chelsea Manning. What she pieced together is a story emblematic of all that was cruel and arbitrary about Gitmo as an institution.

Nabil was a broke, undocumented Algerian immigrant in London who’d moved there while awaiting approval for French citizenship. He’d taken up residence in Afghanistan after being told that "living was cheap, papers were superfluous, and you could study the Qur'an while the bureaucratic wheels churned in France."

He had the misfortune of moving there just months before September 11, 2001, and the subsequent American invasion. In the early days of the war, locals were "rounding up Arabs" after being promised million-dollar bounties by the U.S. military for capturing Al-Qaeda terrorists. Nabil was captured and sold to the U.S. military, which brought him to Guantánamo.

The description of his interrogation there still haunts me:

In the U.S., you're innocent until proven guilty. At Gitmo, the opposite is true. According to his Combatant Status Review Tribunal summary [a cursory review process established in 2004 to "rubber-stamp" the men’s designation, on capture, as "enemy combatants" who could be detained indefinitely], Nabil was a member of al Qaeda. By way of proof, they have only that he was in Afghanistan, owned a gun, and had attended a London mosque known for its extremism. To flesh out his "terrorist" profile, the official summary adds tales of a terrorist training camp and a grenade-filled mountain trench. No member of U.S. forces has ever reported laying eyes on either, but this doesn't matter because the secretive tribunals at Guantánamo allow hearsay as evidence against detainees.

Add in circumstantial evidence, confessions extracted under torture, and "the presumption of regularity," which means the presumption is that U.S. officials are nothing but honest. Following this logic, the truth itself is impossible to prove beyond a reasonable doubt — buried somewhere in the Tora Bora mountains.

Afghans sold Nabil to Afghan forces from his hospital bed. Injured and terrified, he huddled together with five other men in the underground cell of a prison in Kabul. Interrogators whipped him. The screams of the tortured kept him awake at night. According to a statement filed by Clive Stafford Smith, Nabil's lawyer at the time, "Someone — either an interpreter or another prisoner — whispered to him, 'Just say you are al Qaeda and they will stop beating you.'"

This was the justification that kept Nabil imprisoned for 11 years, including four months that he spent "in a metal cage under the burning Cuban sun" while the detention center was being constructed, with nothing but "one bucket for water and another for shit."

I didn’t have the words to articulate it at the time, but after years of absorbing the notion that America had been blessed by divine providence with an infallible justice system, knowledge of Guantánamo had suddenly made that fantasy untenable to me, and I was never really able to believe it again. Here was a person not much older than me who was forced to languish in the same prison as 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed for no reason besides the fact that he happened to be in a certain place and looked a certain way at a certain time.

In hindsight, I understand that something as profoundly wrong and arbitrary as Guantánamo Bay cracked open my ability to process other absurdities and inequalities within our justice system. It was arguably the first time I’d really considered how one’s social, economic, or immigration status could determine whether someone could walk free or would be left to languish in a cell. In the case of Guantánamo Bay inmates, their status as immigrants without the rights to due process afforded to American citizens makes them the perfect targets. And the fact that they are Muslims accused of terrorism, no matter how vague or tangential the link, meant that subjecting them to arbitrary detention and obscene torture could be construed as something grimly necessary or even a virtuous act of righteous vengeance. These were, after all — as the Bush administration frequently put it — "the worst of the worst."

It would take me years more to understand all the numerous ways that proximity to wealth and power can dictate the amount of freedom in one’s life, how race often determines whether someone gets stopped by police or busted for drugs, and their wealth determines whether they can afford a good lawyer or to pay for bail. These disparities in how people experience the criminal punishment system, combined with the overall punitive nature of the system, have created the crisis of mass incarceration in which the U.S. locks up more people than any other nation.

American prisoners are disproportionately people who are poor, Black, experiencing mental illness, or those who have a disability. In other words, they are people who are treated as politically expendable. Similarly, Guantánamo has always stood out to me as one of the most extreme examples of how people’s lives can be totally ruined not because they actually did anything wrong, but because it was simply not politically advantageous for anyone to care what happened to them. Or, conversely, because it was politically advantageous to make an example of them to look tough and serious about stamping out terrorism.

In 2013, when Crabapple visited the prison, the Obama administration — dogged by a looming Congressional report on America’s ugly history of torture during the War on Terror — had an interest in portraying the worst of Guantánamo as something from the past. As Crabapple wrote in another article about a second visit to the camp, this led them to open up the camp for select journalists to go on heavily manicured tours.

She wrote:

Bad Old Gitmo existed from approximately 2002-2007. Its orange jumpsuits, water-boarding, detainees sleeping in what [Montgomery J.] Granger, who served at Guantánamo in 2002, gleefully described as "dog kennels." Its guards pummeling prisoners in revenge for September 11. Bad Old Gitmo, like so many icons of the Bush era, is Not Humane. And "humane" is the catchword of Gitmo now.

With journalists present, officials were sure to highlight all of the wonderful amenities its inmates got to enjoy, as if that somehow made up for their indefinite imprisonment:

Detainees may stay in Gitmo now until they die. But on the bright side, they get condiment packets with their meals: honey and olive oil! Compliant prisoners can take art classes, look at sailing magazines, and even, if they are extremely cooperative, listen to MP3s. Gone, Gitmo officials claim, are the stress positions of former days. Now, if detainees inform on each other, interrogators reward them with pizza.

That was ten years ago. In 2024, it’s easy to forget about Guantánamo Bay. That seems to be by design. Now the approach to Gitmo is less about rebranding and more about avoiding any discussion of it at all. As the Intercept reported last year, visits by journalists to the prison camp are subject to more severe censorship than ever. And in recent years, media interest has fallen to an all-time low.

That lack of attention makes it easy to forget that more than two decades after its establishment as a detention camp for suspects in the War on Terror, 30 men are still being held at Guantánamo without having ever been put on trial.

Many of the families of Guantánamo inmates have spent the last two decades tirelessly advocating for their release. Sanad al-Kazimi, from Yemen, was abducted by the United Arab Emirates and transferred into U.S. custody in 2003 and was subjected to every kind of torture you can imagine. But he was never put on trial for his alleged involvement with Al-Qaeda. He has not seen his youngest son since before the child’s second birthday and has never met his four grandchildren. Despite being cleared for release for close to three years, he has still not been released.

According to a report from the Center for Constitutional Rights:

His wife and his children, now adults, have worked hard to maintain contact with Sanad despite challenges due to the civil war in Yemen. As his son has expressed it: "Oh how I wish to put your hand in my hand and walk together. I wish we could live as any happy family in any happy place."

After four years of Trump, who halted prisoner releases and beat his chest about wanting to send more people to Gitmo, Biden — like his predecessor Obama — initially spoke about finally, mercifully closing down the camp for good. To Obama’s modest credit, he at least got close, releasing 197 (out of 242) detainees to be transferred, repatriated, or resettled in third countries (including Nabil, who was dropped in Algeria just a month after Crabapple’s exposé dropped).

The same cannot be said for Biden, who has overseen the transfer of just ten of the remaining 40 inmates during his term of office. Last week, it was revealed that the Biden administration had been planning to release 11 Yemeni Guantánamo Bay inmates last fall but abandoned the idea after Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel "amid concerns about political optics," according to four U.S. officials who spoke with NBC News. According to the New York Times, none of the prisoners had even been accused of crimes let alone convicted of any. They had all been reviewed by a national security panel and cleared for transfer. And yet, with the plane on the tarmac ready to airlift them to Oman, it was suddenly called off.

According to independent journalist Andy Worthington, for the website Close Guantánamo:

Every month these tallies [of how long these men have been held since being approved for release] become ever more shocking. As of … May 21, these 16 men ha[d] been held for between 606 and 1,300 days since they were approved for release, and, in the three outlying cases based on the deliberations of the Guantánamo Review Task Force, for 5,233 days.

[The poster below shows the latest update, created for the most recent monthly coordinated global vigils for Guantánamo’s closure on June 5].

The 11 Yemenis are among them, and seven months after the cancelled transfer, the Biden administration has not clarified when they will actually be given their freedom. The officials who described Biden’s concern over "optics" also indicated that as the election grows nearer, the chance of Biden releasing these inmates grows slimmer. If Trump wins, then there’s a chance their freedom will be delayed another four years, as he’s previously been totally hostile to letting anyone leave Guantánamo.

As Worthington points out, the decisions on whether to release the men were "made unanimously by high-level U.S. government review processes [and] were purely administrative, and completely outside the U.S. legal system."

He continues:

This not only prevents the men and their attorneys from being able to appeal to a court if the government fails to release them; it also, more crucially, means that they are essentially prisoners of the executive branch, and that, therefore, criticizing the executive runs the risk of endangering their release.

This latest, horrifying news feels so emblematic of how Gitmo has functioned since its inception. The people inside can have their hopes for freedom twisted by the winds of fate, as a result of events purely outside of their control. Just as Nabil was subject to nearly a dozen years of hell just by being in the wrong place at the wrong time and was released by the sheer luck of having been featured in a high-profile piece of journalism, these current inmates are subject to forces entirely beyond their control.

The detainees should have been released last October (if not many years before). The fact that they weren’t has nothing to do with any personal behavior of theirs, but the pure inconvenient politics of the moment. These men had no relation to Hamas’s October 7 attack. They’re from the complete opposite end of the Arabian Peninsula as the people who attacked Israel. (As Kody Cava pointed out in a recent Current Affairs article, such distinctions rarely matter in the U.S.’s fight against "terrorism"). But the "optics" of freeing Muslim men who were at one point or another vaguely associated with "terrorism" — even if there has never been an effort to demonstrate that association — was enough to make it not worth it.

At a time when Islamophobia has reached a similar fever pitch to the Iraq-invading, Freedom Fries-eating, Dixie Chicks-smashing early 2000s, the political cost of appearing even the slightest bit sympathetic to a bunch of scary Muslims (and it should be emphasized that every single one of the 779 inmates held in Guantánamo since 2002 has been Muslim) is too great a risk for Biden to bear in an election year.

Forcing eleven men to wait God knows how much longer for their freedom is worth it to prevent even a minor dip in the polls. Biden surely remembers the risks: When Obama tried to bring Guantánamo inmates to the U.S. — not to set them free, but just to have them stand trial or face indefinite detention — he was furiously rebuked by both parties in the Senate and, according to Pew Research’s News Coverage Index, "terrorism" rocketed to become the number one discussed issue across the news media. Accusations of being a "terrorist sympathizer" dogged him until the day he left office.

Guantánamo Bay is hardly the salient issue it was in Obama’s term. In 2013, the vast majority of Americans were opposed to closing Guantánamo. With the absence of media coverage, closing Guantánamo has virtually fallen off as a relevant political issue and polling about it is scarce. The most recent poll I could find comes from the 20th anniversary of September 11, when around half of respondents said they’d somewhat or partially support closing the prison. So while closing it is hardly radioactive, as it was during the Obama era, Biden hardly has a mandate to fulfill his predecessor’s goal.

The main reason to close Guantánamo Bay is not that it’s particularly politically advantageous. It’s that it’s so flagrantly the right thing to do. I don’t know what to call it when "optics" determine whether a person gets to be free or is forced to rot in jail, but it’s not justice. It’s something that cannot be abided in a country that centers so much of its identity around the premise of equality under the law.