On U.N. Torture Day, Please Support the Guantánamo Survivors, and Those Still Held

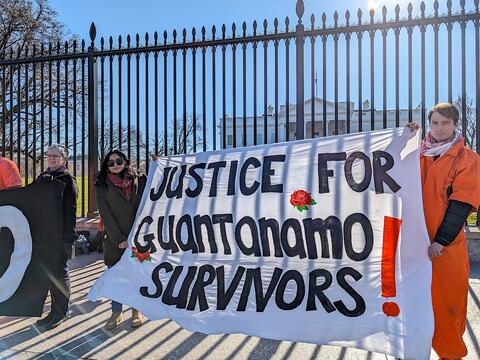

A banner at the vigil for the closure of Guantánamo outside the White House on January 11, 2024. Please click here to support the Guantánamo Survivors Fund's efforts to raise $10,000 to support former prisoners abandoned by the U.S.

By Andy Worthington, June 26, 2024

Today, June 26, is the U.N. International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, introduced in 1997 to mark the tenth anniversary of the historic day in 1987 when the U.N. Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment came into force.

Three days ago, we marked 8,200 days of the existence of a notorious torture facility, the U.S. prison at Guantánamo Bay, with the latest phase of our ongoing photo campaign, which began in January 2018, marking every 100 days of Guantánamo’s existence with posters showing how long it has been open, and urging the president — formerly Donald Trump, but, since January 2021, Joe Biden — to close it.

We were delighted with the response — 56 photos, from opponents of Guantánamo’s continued existence across the US, in the UK, France and Mexico, and in Serbia via former prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, a tireless advocate for the prison’s closure — and we hope that you have time to scroll through what I call "an inspiring snapshot of a cross-section of people — both full-time Guantánamo campaigners, other activists, and even passers-by — who are appalled that Guantánamo is still open, and who, in the U.S., represent a much bigger undercurrent of American society that is largely ignored by the mainstream media."

Some readers may be surprised to see us refer to Guantánamo as a notorious torture facility — not because torture at the prison is unknown, but because the impression given by the media and the U.S. political establishment, when they can be bothered to mention it, is that torture only took place in the "bad old days" of Guantánamo’s early existence, from 2002 to 2004, when two particular prisoners, Mohammed al-Qahtani and Mohamedou Ould Slahi, were singled out for particularly intense torture programs approved by defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and at least a hundred other prisoners (and maybe many more), who were regarded as non-compliant, were also tormented with sleep deprivation, the use of loud music and noise, forced nudity and shaving, painful stress positions, extreme heat and cold, and sexual and religious abuse.

However, although the worst of this abuse came to an end in June 2004, when the Supreme Court ruled that the Guantánamo prisoners had habeas corpus rights, and lawyers were allowed in to begin representing the prisoners, piercing the veil of secrecy that had allowed torture to proceed unchecked, the very existence of a facility devoted to holding people indefinitely without charge or trial, and with no way of knowing if they will ever be freed, can also clearly been seen as a form of torture.

In October 2003, Christophe Girod, a spokesperson for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), broke with protocol to voice the ICRC’s concerns about the conditions of confinement at Guantánamo, stating, "The open-endedness of the situation and its impact on the mental health of the population has become a major problem." In January 2004, the ICRC published an overview of its Guantánamo work on its website, reiterating that it had "observed a worrying deterioration in the psychological health of a large number" of the prisoners.

The fact that Girod spoke out when the prison had been open for less than two years should tell us all something about the psychic burden, over 20 years later, of being held for up to 22 years on the same worryingly open-ended basis, which is the case for the 30 men still held today.

Although ten of these men have been removed from the legal limbo of the prison’s general population, and charged with crimes in its military commission trial system, 19 others are still as fundamentally cast adrift from all legal processes and human rights protections as they were when Guantánamo first opened.

16 have been unanimously approved for release by high-level U.S. government review processes, but are still held because those processes are purely administrative, and no legal mechanism exists to compel the government to release them, if, as has become apparent, the government has proven unwilling to prioritize their release. As of today, these men have been waiting for between 642 days and 1,336 days to be freed, and in three outlying cases for 5,269 days (14 and a half years).

The other three men, out of the 19, are even more abandoned — "forever prisoners" who have also never been charged with a crime, but who have not even been nominally approved for release either.

One other man, who was convicted on terrorism charges in November 2008, after a one-sided trial in which he refused to mount a defense, is serving a life sentence in solitary confinement, which is clearly a form of torture, but even the other men charged in the military commissions are not incorporated into a legal landscape in which any of their fundamental rights are respected.

Their trials are bogged down in endless challenges, as their lawyers seek to expose the full extent of the torture to which they — as the prison’s only "high-value detainees" — were subjected to in CIA "black sites" before their arrival at Guantánamo (mostly in September 2006), while prosecutors continue to try to keep that information hidden.

U.N. assessments: Cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, torture and possible crimes against humanity

The cumulative effect of all of these human rights violations is so severe that, last June, after Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism, became the first U.N. Rapporteur to visit the prison, she issued a devastating report in which she concluded that "the totality of these factors" — in particular, the failure to "provide any torture rehabilitation to detainees" (especially the torture victims of the CIA "black sites"), the continuing violence at the prison as part of its Standard Operating Procedures, the "structural and entrenched physical and mental healthcare deficiencies," the “inadequate access to family," and the "ongoing, arbitrary detention characterized by fair trial and due process violations" — "without doubt amounts to ongoing cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment," and "may also meet the legal threshold for torture."

Regarding torture, what Fionnuala Ní Aoláin’s report made abundantly clear was that, although torture may have taken place in the past, its impacts continue to reverberate on an ongoing basis, especially when, as is apparent at Guantánamo, the authorities have conspicuously failed to provide any kind of torture rehabilitation whatsoever.

Two other devastating opinions were also issued last year by the U.N.’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. The first, in the case of "forever prisoner" Abu Zubaydah, for whom the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program was first developed, found that he was the victim arbitrary detention, in large part because he has never been charged with a crime — as is the case, of course, with the other 18 men who have never been charged. The Working Group also expressed "grave concern" that the very basis of the detention system at Guantanamo — involving "widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law" — "may constitute crimes against humanity."

In a second opinion, the Working Group found that one of the men charged in the military commissions, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, was also the victim of arbitrary detention, concluding that his "rights to fair trial and due process have been repeatedly violated in Guantánamo Bay," and adding that evidence about his treatment suggests that he "suffered the most egregious violations of human rights, of such gravity as to give the deprivation of liberty an arbitrary character."

Life after Guantánamo

Even for those freed from Guantánamo, torture continues to blight their lives. In a section of her report dealing with prisoners freed from Guantánamo, either released in their home countries, or resettled in third countries if repatriation was not possible, because of safety or security issues, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin was withering in her condemnation of the U.S. government’s lackadaisical approach to the care of men released from their custody, finding that there was "little meaningful engagement with the detainees and their legal representatives concerning transfer, which appears to be viewed as an inter-governmental problem to be solved, rather than a rights-endowing process for persons who are torture victims and survivors."

She condemned the lack of a provision to ensure adequate care on release, pointing out that "[m]eaningful healthcare access for torture victim survivors also includes medical and psycho-social provision which can address or manage prior systematic torture as well as health support for family members as secondary victims," and also ran through a roll-call of other inadequacies in the U.S. government’s "diplomatic assurances" with host countries regarding the treatment of resettled prisoners.

In the worst instances — the cases of men transferred to the UAE and Kazakhstan — they have ended up deprived of their liberty. In the UAE, as she noted, "multiple former detainees were subject to arbitrary detention and torture and one remains detained in incommunicado detention" — Ravil Mingazov, whose family were granted asylum in the U.K. — and in Kazakhstan "former detainees effectively remain under house arrest and are unable to live a normal and dignified life due to the secondary security measures put in place post transfer."

Beyond these extreme examples, however, many released prisoners continue to suffer from all kinds of deprivations. As Ní Aoláin found, "access to torture rehabilitation and adequate health care" is not prioritized "in negotiations related to transfer," and she also found that "the existing practice of diplomatic assurances in transfer are generally inadequate to address the economic, social, health, familial, and rehabilitation rights of former detainees, leaving them vulnerable to penury, social exclusion, and sustained governmental inference," as well as, often, being separated from their families, and refused any kind of identification documents whatsoever.

Reviewing the transfer outcomes, Ní Aoláin observed that "no comprehensive provision is made for health care, housing, food, transport, and family needs in U.S. practices of transfer. She found many former detainees and their families to be struggling on every minimal measure of health, employment, family life, and reintegration. Many are unable to work due to the long-term medical and psychological effects of past rendition and torture. Many suffer from severe mental and physical health challenges, and do not have the financial means to access adequate health care. Some men have been rendered homeless despite pleas with the receiving government for assistance."

As she added, "It is simply unacceptable that such men must rely on charity, the support of already overstretched international humanitarian organizations, or the fundraising of their lawyers to get by," and yet, until hopefully one day the U.S. government is held accountable for its crimes, many of these men are indeed reliant on the financial assistance of individual supporters around the world.

The logo of the Guantánamo Survivors Fund.

The Guantánamo Survivors Fund

In the U.S., a group of these supporters, from grass-roots organizations including Witness Against Torture and No More Guantánamos, established the Guantánamo Survivors Fund in April 2022, to provide "immediate short-term support for [the] most urgent needs" of some of these men, including help with medical care, rent, language classes, tuition, and job training, and with former prisoner Mansoor Adayfi providing important assistance in identifying those in need.

As they explain on their website, since their founding they have raised more than $100,000 to help over 30 former prisoners and their families, and some examples of what they have provided can be found here.

On U.N. Torture Day, the Guantánamo Survivors Fund is hoping to raise $10,000 to continue its vital work, making reparations for the U.S. government’s own failures to adequately address the needs of men released from their custody after years of torture and abuse. If you can help out at all, please do make a donation.