Slow Murder at Guantánamo as Profoundly Disabled Torture Victim Is Sentenced to Another Eight Years

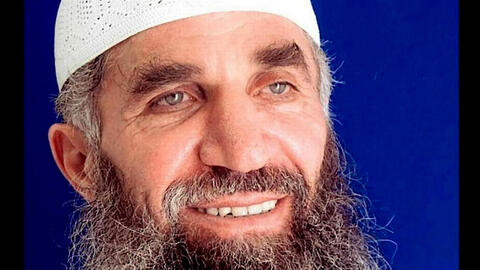

Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi (Nashwan al-Tamir), in a photo taken at Guantánamo in recent years by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, July 15, 2024

Three weeks ago, a grave injustice took place at Guantánamo, when Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, a 62- or 63-year old Iraqi citizen whose real name is Nashwan al-Tamir, and who is Guantánamo’s most profoundly disabled prisoner, was given the maximum sentence possible by a military jury at his sentencing for war crimes in the prison’s military court. The jury gave him a 30-year sentence, although, under a plea deal agreed in June 2022, that was reduced to ten years, meaning that he will not, apparently, be freed from the prison until June 2032.

The reason this is a problem is that al-Iraqi suffers from a chronic degenerative spinal disease, which has not been been dealt with adequately despite the seven surgical interventions he has received in the medical facilities at Guantánamo. Shamefully, prisoners are forbidden, through U.S. law, from being transferred to to the U.S. mainland to receive specialist medical treatment even though grave physical problems like al-Iraqi’s cannot be properly addressed in Guantánamo’s limited medical facilities. All of these problems were highlighted in a devastating 18-page opinion about al-Iraqi’s treatment, which was issued by a number of U.N. Special Mandates on January 11, 2023, the 21st anniversary of the prison’s opening, and which I wrote about here.

The sentence seems particularly punitive because there is no guarantee that al-Iraqi will even survive until 2032, and it is certainly possible, if not probable that, if he does survive, he will by then be completely paralyzed. Two years ago, when the plea deal was announced (which I wrote about here), sentencing was delayed for two years to allow the U.S. government "to find a sympathetic nation to receive him and provide him with lifelong medical care," and also to hold him while he serves out the rest of his sentence, as Carol Rosenberg explained at the time for the New York Times, given that he cannot be repatriated because of the security situation in Iraq.

As Susan Hensler, his Pentagon-appointed civilian attorney, also explained at the time, "He pleaded guilty for his role as a frontline commander in Afghanistan. He has been in custody for 16 years [now 18], including the six months he spent in a CIA black site. We hope the United States makes good on its promise to transfer him as soon as possible for the medical care he desperately needs."

The U.S. government now has eight years to find a host country that will look after him for the rest of his life, having evidently failed to do so in the last two years. Any host country will presumably expect to be handsomely rewarded for doing so, but the U.S. government will have no choice but to try, because, unlike almost every other prisoner at Guantánamo, whose release is essentially optional, those who agree to plea deals enter into agreements that are legally binding.

Who is Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi?

A Kurd born in Mosul, al-Iraqi served as a Major in the Iraqi Army during the Iran-Iraq War in 1980-88, and then traveled to Afghanistan after Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1991, where he married an Afghan woman and had children. By the time of the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he was evidently a military commander in charge of men fighting against U.S. forces, although he was not captured until October 2006, when he was in Turkey, allegedly — according to the U.S. government — en route to Iraq where he had been brokering negotiations between Osama bin Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

After spending roughly six months in secret CIA custody in Afghanistan — despite the alleged closure of the "black sites" after 14 "high-value detainees" were transferred to Guantánamo in September 2006 — al-Hadi was one of the last prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo, in March 2007, when he was described as "a high-level member of al-Qaeda," and "one of al-Qaeda’s highest-ranking and experienced senior operatives," and was imprisoned as a "high-value detainee" (HVD) in the secretive Camp 7 where the other HVDs were held, completely separate from the prison’s general population.

It took another six years from him to be charged, when as Carol Rosenberg described it in 2022, it was claimed that he "was part of the sweeping Qaeda conspiracy to rid the Arabian Peninsula of non-Muslims," that he had knowledge of the 9/11 attacks, and was involved in "the destruction by the Taliban of monumental Buddha statues in Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley, a UNESCO World Heritage site, in March 2001," and "the 2003 assassination by insurgents of a French worker for the United Nations relief agency."

By the time of his plea deal, however, most of the above had been dropped — "a drastic scaling back" of the government’s charges in Carol Rosenberg’s words — suggesting that most of it was unreliable, although al-Iraqi dutifully signed an 18-page plea deal, in which, as Rosenberg described it, he "admitted to conspiring with Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida starting in 1996," and to helping the Taliban blow up the Bamiyan Buddha statues.

Mostly, however, terrorism took a back seat to admissions of war crimes associated with his role as a military commander. As Rosenberg described it, he "pleaded guilty to the traditional war crimes of attacking protected property — a U.S. military medevac helicopter that insurgents who answered to him failed to shoot down in Afghanistan in 2003 — and of treachery and conspiracy connected to insurgent bombings that killed at least three allied troops, one each from Canada, Britain and Germany."

The military judge, Lt. Col. Mark F. Rosenow, stated, "Those allied soldiers were killed by car bombs or suicide bombers posing as civilians … If Mr. Hadi had known in advance about the plans, he had a duty to stop them. If he had possessed no prior knowledge, [he] had a duty to punish the perpetrators."

Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi’s sentencing

For the sentencing, the prosecutors invited wounded soldiers and the family members of soldiers killed in Afghanistan to testify about the enduring impact on them of the actions undertaken by men under al-Iraqis’s command, for which al-Iraqi himself apologized in a 90-minute presentation on June 17 to family members and the 11-strong military jury.

As Rosenberg described it, he spoke "from a padded therapeutic chair he uses because of [his] paralyzing spine disease," and "slowly read an unclassified English language script, stopping at times to regain his composure or wipe tears from his eyes."

"As the commander I take responsibility for what my men did," he said, adding, "I want you to know I do not have any hate in my heart for anyone. I thought I was doing right. I wasn’t. I am sorry."

Speaking directly to the family members, he also said, "I know what it is to watch another soldier die or get wounded. I know this feeling and I am sorry. I know you suffered too much."

As Rosenberg described it, he also "appeared to single out a Florida man, Bill Eggers, who spoke of losing his firstborn son, a commando, in a roadside bomb set by Mr. Hadi’s troops in 2004," telling him, "I know what it is to be a father of a son. To lose your son — your sadness must be overwhelming. I am sorry."

Al-Hadi also spoke about the CIA "black site" in which he was held in Afghanistan, after his capture, featuring "forensic photography" of his cell, "a 6-foot-square empty chamber" known as "Quiet Room 4," which had been disclosed to defense lawyers by prosecutors, and which was the first time that the interior of a "black site" prison had been seen.

As Rosenberg wrote, "He described being blindfolded, stripped, forcibly shaved and photographed naked on two occasions after his capture in 2006. He never saw the sun, nor heard the voices of his guards, who were dressed entirely in black, including their masks."

As she proceeded to explain, "At first he was held in a windowless cell with a built-in, stainless steel shower and toilet, as shown in the visual presentation in court. He was moved after months of constant questioning about the location of Osama bin Laden, which he said … he did not know. The next cell, shown in court, was empty, without a toilet or shower — just three shackle points on the walls. For the three months he was held there, Mr. Hadi said, it had a thin mat on the floor, a bucket for a toilet and a splash of bloodstain on one wall. At one point, he said, his food ration contained pork, which is forbidden in Islam. He refused to eat and became so weak that he could not stand. His captors then brought him a nutritional substitute, Ensure."

He added that he "did not have a clock to know when to pray," and described his time in the "black site" as "the most humiliating experience of his time in U.S. custody."

Nevertheless, Rosenberg added, although he "described his conditions as cruel," he added that "his experience as a prisoner of the United States had been tempered by remorse and forgiveness."

As Rosenberg proceeded to explain, "He described his 17 years incarcerated at Guantánamo as lonely at times, an isolating experience" that was, nevertheless, "interspersed with individual acts of goodness."

He noted that, "while recovering from his surgeries," prison staff nurses "cared for me with gentle kindness," further explaining that, at a time when he was left paralyzed, a U.S. military doctor "helped get him accommodations in his prison cell," and "would come to play checkers with me, stay with me during my recovery from surgery."

Closing arguments

On June 19, the prosecution and defense presented their closing arguments, and the jury began its deliberations. The lead prosecutor, Douglas J. Short, who had started on the case a decade ago as a Navy reservist, and had continued as a civilian after his military appointment ran out, called al-Iraqi a "senior member of one of the most notorious conspiracies to date, Al Qaeda," and "offered a timeline of the deaths of 17 U.S. and foreign coalition soldiers in 2003 and 2004," in Carol Rosenberg’s words, for which, he said, al-Iraqi was responsible.

These were war crimes, he said, because, as Rosenberg described it, "the Taliban and Qaeda forces who carried them out blended in with the civilian population and used unorthodox methods of warfare, such as turning civilian taxis into bombs by packing them with explosives." As Douglas Short put it, "He had his men feign civilian status to invite confidence, and then betray that confidence."

In contrast, the closing argument for al-Iraqi was delivered by Maj. Lucas R. Huisenga, who "joined the defense team last summer," after he "served two tours in Iraq between 2003 and 2006, as an enlisted Marine infantryman and scout sniper, and then left the service to become a lawyer."

Maj. Huisenga told the jury that what al-Iraqi had done "was not terrorism — it was war," admitting, however, that al-Iraqi’s men, following his command, "fought and killed coalition forces" using "guerrilla tactics that violated the laws of warfare." He added that these were "serious" crimes, but insisted that al-Iraqi "did not abandon" the rules of warfare entirely, because he "instructed his troops to spare civilians."

In addition, Maj. Huisenga described Mr. al-Iraqi as a "broken man," who, "as a result of his spine disease and unsuccessful surgeries at Guantánamo", in Rosenberg’s words, "is in 'terrible physical health' and in constant pain." As he put it, he "walked into U.S. custody and will not be able to walk out of it."

As Rosenberg also explained, "In an analogy not heard before in the 10-year-old case, the major likened Mr. Hadi’s 'guerrilla warfare' to tactics used by U.S.-backed Ukrainian forces trying to repel the Russian invasion." Maj. Huisenga "also told the panel that Mr. Hadi had fled his native Iraq in 1990 and had been drawn to the jihad in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion, when U.S.-backed, anti-communist forces also used guerrilla tactics."

In Rosenberg’s words, "He portrayed Mr. Hadi as a combatant who, after marrying an Afghan woman and having children, lived among Afghans, not in Qaeda compounds. When the Qaeda leadership fled Afghanistan after the Sept. 11 attacks, Mr. Hadi stayed to fight the 'occupation of his adopted homeland.'"

When it came to the sentencing, the jury handed down the maximum sentence available, 30 years, rejecting his defense team’s arguments that, as Rosenberg described it, "he deserved leniency, if not clemency, for his early humiliations in CIA custody, subsequent cooperation with U.S. investigators and failing health."

Despite this, in practical terms the sentence is fundamentally irrelevant, because of the ten-year sentence already agreed by the commissions’ Convening Authority, although questions must surely remain about whether it is appropriate for al-Iraqi to have been convicted for war crimes at all, when these crimes so clearly only came to the fore because of the failure to find any examples of terrorism for which he could be convicted, and especially, I think, because of his evident contrition.

As Jeffrey St. Clair noted in an article for Counterpunch, "Ultimately, Al-Hadi’s contrition, remorse and failing body, crippled by years of torture and confinement, did little to sway an 11-member, anonymous U.S. military jury, which … handed down the maximum sentence of 30 years in prison for committing the same kind of war crimes the U.S. and its allies have committed with impunity for decades, including crimes against Al-Hadi himself."