Lloyd Austin Cynically Revokes 9/11 Plea Deals, Which Correctly Concluded That the Use of Torture Is Incompatible With the Pursuit of Justice

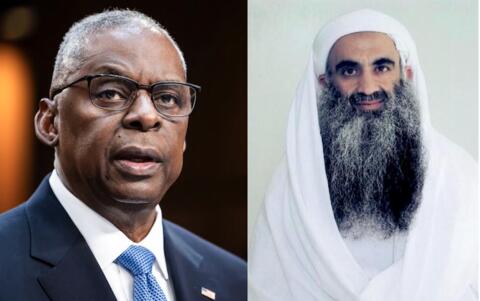

U.S. defense secretary Lloyd Austin and Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, photographed in recent years at Guantánamo.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, August 3, 2024

In depressing but sadly predictable news regarding the prison at Guantánamo Bay and its fundamentally broken military commission trial system, the U.S. defense secretary, Lloyd Austin, has stepped in to torpedo plea deal agreements with three of the men allegedly involved in planning and executing the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, which were announced just 48 hours before in a press release by his own department, the Department of Defense.

The three men in question are Khalid Shaikh Mohammad (KSM), the alleged mastermind of the attacks, Walid Bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, and, although the full details of the plea deals were not made publicly available, prosecutors who spoke about them after the DoD’s press release was issued confirmed that the three men had "agreed to plead guilty to conspiracy and murder charges in exchange for a life sentence rather than a death-penalty trial."

The plea deals, approved by the Convening Authority for the military commissions, Army Brig. Gen. Susan Escallier, who was previously the Chief Judge in the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals, would finally have brought to an end the embarrassing and seemingly interminable efforts to prosecute the three men, which began sixteen and a half years ago, and have provided nothing but humiliation for four successive U.S. administrations — those led by George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

When the plea deals were announced, those who believe in justice and the law — myself included — were relieved that, after so many years in which the U.S. government obstinately refused to accept that it was delusional to think that successful prosecutions, and the delivery of the death penalty, were possible in the cases of men that they themselves had previously subjected to excruciating torture in a global network of CIA "black sites," they represented a fundamental concession by the government that the use of torture, instigated not only in the "black sites," but also in U.S. military prisons in Afghanistan, at Guantánamo, and later, in Iraq, was, and is fundamentally incompatible with the pursuit of justice.

To provide some necessary context, the three men were captured in two separate house raids in Pakistan in March 2003, and then spent three and a half years in CIA "black sites" before arriving at Guantánamo, with eleven other men also held in the "black sites," and all known collectively as the "high-value detainees."

Imprisoned away from the general population at Guantánamo, in a shadowy facility known as Camp 7, they were first charged in February 2008 with three other men, were arraigned in June 2008 (after one of those cases had been dropped because of a concession by the then-Convening Authority, Susan Crawford, that he had been tortured at Guantánamo), and were then charged again in June 2011, and arraigned again in May 2012, after the Obama administration, which had announced its intention, in November 2009, to try them in federal court in New York, feebly backtracked on those plans after criticism from Republican lawmakers.

For the last 12 years, their cases have been caught up in pre-trial hearings, as their lawyers have sought to extract information from the government regarding their torture, which, they have correctly and persistently argued, was essential if there was to be anything resembling a fair trial, while prosecutors have sought to keep that information hidden, largely, it seems, to protect the CIA.

I have frequently described this seemingly never-ending process as being akin to "Groundhog Day," and the government’s obsession with secrecy, and often with hiding information from the defense teams, has been maintained throughout this period, even as crucial information about the men’s treatment has publicly emerged, most notably via the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report about the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program, which was released in December 2014.

The evolution of the plea deals

Plea deals as a way of resolving the seemingly insurmountable tension between the use of torture and the pursuit of justice had first been proposed in 2017 by the then-Convening Authority, the law professor Harvey Rishikof and his deputy, Air Force Col. Gary Brown, who had been negotiating with the men’s lawyers, and had been the first to propose that, if they agreed to plead guilty, the death penalty would be taken off the table, and they would be given a life sentence instead.

For their efforts, they were unceremoniously sacked, and it was not until May 2022 that the plea deals publicly resurfaced, after prosecutors reportedly recognized the impossibility of their task in the wake of the sentencing of Majid Khan, another "high-value detainee," who had been recruited by Al-Qaeda as a money courier, when he was at a low point in his life following the death of his mother.

Cooperative and remorseful from the moment he was seized — also in Pakistan, in March 2003 — Khan was, nevertheless, persistently subjected to torture, which he described in a statement that he was allowed to make at his sentencing hearing, in October 2022, and which was so shocking that seven of the eight members of his military jury called for clemency, comparing his torture to that "performed by the most abusive regimes in modern history."

While prosecutors were aware that the 9/11 co-accused hadn’t demonstrated remorse as Khan had, the military jury’s response to Khan’s statement evidently made them acutely aware that the five men charged in connection with the 9/11 attacks had been subjected to torture that plumbed even more depraved depths than that to which Khan was subjected, and that plea deals were the only practical way to keep the extent of that torture out of the public spotlight.

Much of this was spelled out in the Senate Intelligence Committee report, and was also helpfully summarized in profiles on the website of The Rendition Project (see here for KSM, here for Bin Attash, and here for al-Hawsawi). However, the most noticeably shocking aspects of their torture had also been widely reported in the media for many years — the fact that KSM was subjected to waterboarding, an ancient form of water torture, which involves controlled drowning, on 183 separate occasions, and the fact that, as established through the Senate report’s analysis of CIA records, al-Hawsawi was subjected to "rectal exams conducted with'‘excessive force'" in a "black site" in Afghanistan, and, as a result, was later "diagnosed with chronic haemorrhoids, an anal fissure, and symptomatic rectal prolapse."

In addition, what was also of increasing concern to prosecutors was the possibility, or even the probability that the bulk of the evidence against the 9/11 co-accused — confessions obtained in the "black sites" — might be fatally tainted through the use of torture. This concern came to a head last summer, when Col. Lanny J. Acosta Jr., the military judge in another case, that of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, another "high-value detainee," accused of masterminding the terrorist attacks on the USS Cole in 2000, which killed 17 U.S. sailors, ruled as inadmissible confessions made by by al-Nashiri to a supposed "clean team" of interrogators after his arrival at Guantánamo in September 2006, which, the authorities had hoped, would remove the taint of torture that clung to confessions that he had previously made in the "black sites."

As I explained at the time, "At the heart of Col. Acosta’s measured and devastating opinion [was] an appalled recognition that the extent of al-Nashiri’s torture, and its location with a system designed to break him and to make him entirely dependent on the whims of his interrogators to prevent further torture, made it impossible for him to have delivered any kind of uncoerced self-incriminating statement to the 'clean team' who interviewed him in 2007."

As I also explained, Col. Acosta’s ruling also "cast a shadow over the prosecution of the five men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, who were also subjected to 'clean team' interrogations after their arrival at Guantánamo from the 'black sites.'" These statements had been ruled as inadmissible in August 2018 by the then-judge in the 9/11 trial, Army Col. James L. Pohl, who had been the judge on the case since the men’s arraignment in 2012, and who delivered his ruling as he also announced his retirement. However, his successor, Marine Col. Keith Parrella, reinstated them in April 2019, and Parrella’s successor, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, has been embroiled in the ongoing conflict regarding the admissibility of "clean team" statements since he took over from Parrella in September 2021.

Lloyd Austin’s lamentable decision to withdraw Susan Escallier’s authority to agree to the plea deals, in which he rather pompously "determined that, in light of the significance of the decision to enter into pre-trial agreements with the accused," the "responsibility for such a decision should rest with me as the superior convening authority under the Military Commissions Act of 2009," does nothing but hurl the 9/11 case back into a legal abyss, as well as committing the government to continue haemorrhaging billions of dollars in prosecuting a case that is fundamentally unwinnable, however much its supporters pretend otherwise.

These include the usual Republican suspects, who denounced plans for a federal court trial back in 2009, and who have been joined by more recent enthusiasts for lawlessness like Donald Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, who stated, "We need a president who kills terrorists, not negotiates with them," almost as though he was suggesting that extrajudicially removing them from their cells and summarily executing them would be an acceptable outcome.

Sadly, however, Austin’s decision primarily seems to turn the clock back to September 2023, when, reportedly, President Biden refused to endorse the plea deals negotiated at that time, which included what the New York Times described as the defendants’ request for "a civilian-run program to treat sleep disorders, brain injuries, gastrointestinal damage or other health problems" associated with their torture, and "assurances they would not serve their sentences in solitary confinement and could instead continue to eat and pray communally — as they do now."

At the time, Biden reportedly "adopted a recommendation" by Austin "not to accept the 'joint policy principles,'" as the proposals were known, with one official who spoke to the Times stating that he "did not believe the proposals, as a basis for a plea deal, would be appropriate," while another "cited the egregious nature of the attacks."

What will happen now is currently unknown — whether, for example, Susan Escallier, so publicly rebuked by Lloyd Austin, who must have known about her decision, will resign, and whether prosecutors, also snubbed, will resign, but it already clear that legal appeals will be made against "undue command influence" on Austin’s part. In a suitably bullish press release, Anthony D. Romero, the executive director of the ACLU, stated, "By revoking a signed plea agreement, Secretary Austin has prevented a guilty verdict in the most important criminal case of the 21st Century. This rash act also violates the law, and we will challenge it in court."

He added, "It's stunning that Secretary Austin betrayed 9/11 family members seeking judicial finality while recklessly setting aside the judgment of his own prosecutors and the Convening Authority, who are actually steeped in the 9/11 case. Politics and command influence should play no role in this legal proceeding. Yet, Secretary Austin dishonored an agreement reached after years of hard work and painstaking consultation by all the parties involved. It's also more than a little ironic that Secretary Austin’s gung-ho insistence on executing the 9/11 defendants directly contradicts the Biden Administration’s public commitment to ending the death penalty. The United States has spent decades and tens of millions of dollars trying to secure a death sentence that cannot be upheld in the face of the government’s torture."

Despite this, the limbo provoked by Austen’s capitulation is appalling, serving only to placate Republican critics, whose ongoing desire for vengeance is seemingly insatiable, and also noticeably dealing a blow to the U.S. government’s responsibilities, under international humanitarian law, to treat its prisoners humanely.

The U.S.’s ongoing and flagrant abuse of prisoners at Guantánamo

When Biden and Austin reportedly took exception to the men’s request last year for "a civilian-run program to treat sleep disorders, brain injuries, gastrointestinal damage or other health problems" associated with their torture, their indifference was a major rebuke to high-level criticism that, under international humanitarian law, all they were asking for was what the U.S. government should have been providing for them throughout their detention, but, shamefully, had deliberately failed to do.

That high-level criticism was delivered last year by a U.N. Rapporteur — Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism — after she had finally become the first U.N. Special Mandate holder to be able to visit Guantánamo, when she seemingly startled the administration not only by concluding that the entire detention system "amounts to ongoing cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment," which "may also meet the legal threshold for torture," but also by specifically taking aim at the the failure to "provide any torture rehabilitation to detainees," and at the prison’s "structural and entrenched physical and mental healthcare deficiencies."

Ní Aoláin’s trenchant criticisms, while very evidently applying to all 30 of the men still held at Guantánamo, are of particular relevance, regarding torture rehabilitation, with reference to the "high-value detainees" subjected to such long and gruesome torture in the CIA "black sites" — men who, as well as KSM, Walid Bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, also include the two other men charged in connection with the 9/11 attacks, but not part of the now-aborted plea deals: Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Ammar al-Baluchi.

In bin al-Shibh’s case, he was so broken by the torture to which he was subjected that, last year, a DoD Sanity Board found that he was unfit to stand trial because he suffered from "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), with Secondary Psychotic Features," and also suffered from a "Persecutory Type" of "Delusional Disorder." The ruling led Col. McCall to sever his case from the other four co-accused, leaving him in a legal limbo whose implications have not been addressed by the authorities in the last year.

In al-Baluchi’s case, meanwhile, his lawyers, including the formidable James Connell and Alka Pradhan, have been engaged in separate negotiations regarding a plea deal, which are now presumably looking as threatened by undue influence from the top as the suppressed arrangements for KSM, Walid Bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi.

A nephew of KSM, al-Baluchi suffers from brain damage as a result of being used as a training prop in the "black sites," when he was repeatedly slammed against a wall as an example of one of the torture techniques approved for use on the "high-value detainees," and Connell, his lead lawyer, told the Lawdragon website that his legal team were were "still pushing for 'an official recognition' of the torture he endured," which "could include a government decision not to use the incriminating statements al-Baluchi gave to the FBI [the so-called 'clean team'] after arriving [at] Guantánamo," and emphasized that the "most important" aspect of the ongoing negotiations involved "treatment for the consequences of [the] torture" to which he was subjected.

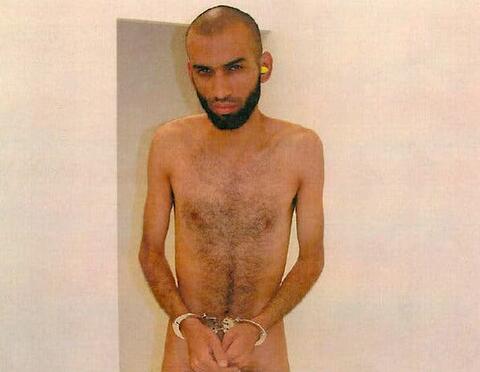

An emaciated Ammar al-Baluchi, photographed by the CIA at a "black site" in 2004.

Ironically for the Biden administration, just as Lloyd Austin was preparing to announce his dismissal of Susan Escallier’s plea agreements, throwing the future of al-Baluchi’s ongoing negotiations into doubt, his lawyers released to the media a truly shocking photo of him, naked and emaciated at the "black site" in Lithuania, in early 2004, just before the Abu Ghraib photo scandal broke, which was obtained through litigation at Guantánamo, and is the very first "black site" photo made publicly available from the 14,000 taken in total by CIA operatives, the rest of which remain classified.

If Guantánamo wasn’t such a backwater for outrage, the photo of al-Baluchi would surely prompt immediate calls for his release, and for those responsible for his treatment to be held accountable, but in the morally broken world in which we currently find ourselves, it seems unlikely that the release of the photo will cause anything more than the mildest ripples of disgust.

What needs to happen now

Surveying the legal landscape of Guantánamo after Lloyd Austin’s shameful capitulation to what can best be described as the U.S. government’s obsession with endless vengeance when it comes to its "black site" prisoners, it seems clear not only that Austin should allow the plea deals to proceed, but the DoD should also recognize the need for a plea deal to be successfully negotiated for Ammar al-Baluchi. It should also drop the proposed prosecution of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri and negotiate a plea deal with him too, following a devastating opinion delivered last year by the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, which condemned his long imprisonment as arbitrary, and also condemned the torture to which he was subjected, and which led an independent expert, Dr. Sondra Crosby, to describe him as "one of the most severely traumatized individuals" she had ever seen.

Of the four other active cases in the military commissions, three have also already led to plea deals, in the cases of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, Guantánamo’s most profoundly physically disabled prisoner, and Mohammed Farik Bin Amin and Mohammed Nazir Bin Lep, accomplices of Hambali (Riduan Isamuddin), the alleged leader of the South East Asia terror group Jemaah Islamiyah, whose case may also best be concluded via a plea deal.

As for Ramzi bin al-Shibh, he should evidently be freed, if a country can be found that is prepared to offer him lifelong mental health care that he needs, and, if that is impossible to arrange, he should receive that care at Guantánamo.

In addition, just as Ammar al-Baluchi’s lawyers have been seeking assurances that he will receive "treatment for the consequences of [the] torture" to which he was subjected, so too must this treatment be extended to all the survivors of the CIA’s "black site" torture program, including KSM, Walid Bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi.

Somehow, when Fionnuala Ní Aoláin delivered her devastating criticism of the prison last year, the Biden administration seemed not to realize that, in the cases of Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Ammar al-Baluchi, it had singularly failed to provide any rehabilitation for the severe mental health problems arising from their torture, or the severe physical problems of the rape victim Mustafa al-Hawsawi and of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, who is close to total paralysis after seven operations in the hospital’s inadequate medical facilities, which have failed to properly address the severity of the chronic degenerative spinal disease from which he suffers.

As well as providing the necessary physical and mental health care for all of the men with active military commission cases — and for all of the 30 men still held at Guantánamo — the Biden administration also needs to take urgent steps to free the 16 men still held who have long been approved for release, and also to release the three "forever prisoners" — men who have neither been charged nor approved for release — who include Abu Zubaydah, for whom the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program was first invented, in the mistaken belief that he was a high-ranking member of Al-Qaeda.

Last year, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention delivered a devastating opinion in his case, concluding that his ongoing imprisonment was arbitrary, and also expressing "grave concern" that the very basis of the detention system at Guantánamo — involving "widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law" — "may constitute crimes against humanity."

Last month, in his Periodic Review Board hearing — the parole-type system established under President Obama to decide whether it was safe to free men who were otherwise held indefinitely without charge or trial — Solomon Shinerock, one of his lawyers, told the panel hearing his case that, as Margot Williams explained for the Intercept, a third country that wasn’t named "could admit Abu Zubaydah and monitor his activities indefinitely," and that Zubaydah himself, who is effectively stateless, having been born in Saudi Arabia to Palestinian parents, "will agree to any form of surveillance by the host country."

If Biden wants to salvage any kind of legacy for doing the right thing, he should not only put aside the obsession with perpetual vengeance that fuels Guantánamo’s unending injustice, and make sure that the plea deals are reinstated; he should also move swiftly to ensure that all of the men approved for release, as well as the "forever prisoners," are freed before he leaves office, leaving just ten or eleven men held at Guantánamo, at a fraction of the cost of half a billion dollars a year that it currently costs to keep the prison in business — most of which is spent on the military commissions.

The cost of treating these men adequately, as most of them live out the rest of their lives in the remains of the U.S.’s most flawed experiment in legal barbarism in the 21st century, may seem like some sort of moral weakness to a country so marinaded in violence and vengeance, but, if he can find the courage, it will be remembered as the opposite — a principled attempt to redress the malignant folly at the heart of the detention policies undertaken in the "war on terror": responding to terrorism with torture.