Guantánamo Resettlements in Turmoil as Oman Forcibly Repatriates Yemenis Given New Homes Between 2015 and 2017

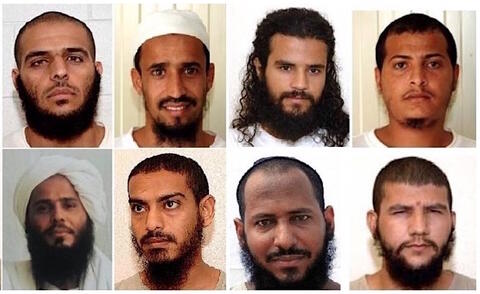

The eight Yemenis who were resettled in Oman from Guantánamo in January 2017, following the resettlements of 20 other Yemenis in 2015 and 2016. Almost all have now, shamefully, been forcibly repatriated to their home country.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, August 14, 2024

In genuinely dispiriting news, Spencer Ackerman has reported, via his Forever Wars website, that the majority of the 28 former Guantánamo prisoners from Yemen who were resettled in Oman between 2015 and 2017 have been forcibly repatriated to their home country over the last few weeks.

The news is particularly dispiriting because, until now, the Sultanate of Oman had appeared to be one of the most successful countries involved in resettling former Guantánamo prisoners, all unanimously approved for release by high-level U.S. government review processes, but who could not be safely repatriated.

This was either because the State Department regarded it as unsafe for them to be sent home (on the basis of human rights concerns, or concerns about their potential recruitment or targeting by forces hostile to the U.S.), or because provisions inserted by Republicans into the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) proscribe certain countries, including Yemen, from receiving their citizens (again, for reasons of national security), or, in a few cases, because they were essentially stateless.

The essential background to the Guantánamo resettlement program

Throughout the eight years of the Obama presidency, 125 former Guantánamo prisoners were resettled in 28 countries around the world, including many in the E.U., some in the countries of the former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, and the occasional outlier elsewhere, including Ghana, Senegal and Uruguay. The largest numbers, however, were taken in by two countries in the Middle East — Oman (30) and the United Arab Emirates (23). I wrote about all of these releases at the time, which you can find here, amongst the 109 articles I’ve published about prisoner releases from Guantánamo since 2007.

These men were from a variety of countries, including Egypt, Libya, Syria and Uzbekistan, although nearly half (61 in total) were Yemeni citizens, whose repatriation was banned not only in the NDAA, but also by the Obama administration, after a Nigerian citizen, allegedly connected to the Al-Qaeda offshoot Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, tried and failed to blow up a plane bound for the U.S. with a bomb in his underwear in December 2009.

Others included 17 Uighurs, from China’s Xinjiang province, who had all been rounded up mistakenly, because their only enemy was the Chinese government, four essentially stateless Palestinians, who couldn’t be repatriated because Israel refused to allow them to return, and, in the latter years, a number of Afghans, after Republicans added Afghanistan to their list of proscribed countries.

The Uighurs, in particular, were extremely difficult to resettle, because of Chinese hostility, which meant that only countries that weren’t intimidated by China were prepared to help. After five Uighurs and a lone Egyptian were accepted as refugees by Albania in 2006 — the only men resettled in third countries under George W. Bush, who was particular adept at releasing men to their home countries (almost two-thirds of Guantánamo’s 779 prisoners were freed during his time in office) — the 17 Uighurs freed under Obama ended up in Bermuda, Palau, Switzerland, El Salvador and Slovakia.

Arranging these resettlements was a significant diplomatic task, undertaken by various State Department officials in Obama’s first 18 months in office, when a charm offensive based on his popularity secured around 40 of the resettlements, and followed up in his second term through the establishment of a specific role in the State Department, the Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, whose two post-holders (Cliff Sloan, from 2013-14, and Lee Wolosky, from 2015-17), along with another Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, Paul Lewis, who was appointed to the DoD, spent a considerable amount of time and effort wooing potential host countries, and working out what favors they might want for helping the U.S. out of a hole of its own making.

Resettling prisoners on the U.S. mainland, as would have been fitting, was ruled out in 2009, after Republicans scuppered plans to resettle some of the Uighurs in Virginia, prompting the first insertion of provisions into the NDAA banning any Guantánamo prisoner, or any former Guantánamo prisoner from setting foot on U.S. soil for any reason whatsoever.

Dangerously failed resettlements

The resettlement deals involved "diplomatic assurances" that the men would be treated humanely, although the specific details of the deals were secret, and in reality some men were treated better than others. The Western European countries have generally treated their former prisoners well, but elsewhere the results have been mixed.

The most glaring examples of failed resettlement programs have, to date, involved three countries in particular — Kazakhstan, Senegal and the United Arab Emirates, although many others, though not as extreme, could also be cited.

In Kazakhstan, where five men were resettled in December 2014, one died of medical neglect four months later, while another, also severely ill, was allowed to leave Kazakhstan for Mauritania, but also died after he was unable to secure the medical treatment he required in either country. The others, meanwhile, have endured nearly a decade of being treated without any fundamental rights.

As one, the Yemeni artist Sabri Al-Qurashi, explained last year, "I have no official status, no ID card, no right to work or education, and no right to see my family." Supported by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), he has been told that he has no rights because he is "illegal," a fundamental betrayal of the "diplomatic assurances" that, as a former State Department official explained, were supposed to involve the provision of "housing, access to medical care, educational opportunities, the ability to work, and the opportunity to start or reunify with their families."

In Senegal, two Libyans resettled in April 2016 were forcibly repatriated two years later. One went willingly, in the hope of being reunited with his family, but the other said he would have stayed in Guantánamo if he had known in advance of the betrayal of the “diplomatic assurances” he received. In the end, both men were seized and imprisoned by militias on their return to Libya before their eventual release, although the NGO Reprieve explained in January 2022 that they remained "vulnerable to re-detention."

In the UAE, 23 men were taken in between 2015 and 2017 — 18 Yemenis, four Afghans and a Russian, Ravil Mingazov, who, the State Department correctly concluded, couldn’t be safely repatriated. All the men were promised that, after a brief period of "rehabilitation," they would be helped to rebuild their lives, but instead they found themselves imprisoned, largely incommunicado, in circumstances that were more abusive than what they had left behind in Guantánamo.

Eventually, the Emirati authorities tired of imprisoning the men, and, despite repeated interventions by U.N. Rapporteurs, sent them back to their home countries, with a flagrant contempt for both the security concerns and the human rights concerns of the U.S. government, even though this was why they hadn’t been repatriated in the first place. The Yemenis were sent back in July and October 2021, while Mingazov, despite a campaign to reunite him with his family, who were granted asylum in the U.K., was forcibly repatriated to Russia just last week.

Of particular concern, from a human rights perspective, was the danger that repatriation posed to the returned Yemenis, and that it poses right now to Ravil Mingazov, on the basis that they contravene the principle of non-refoulement, enshrined in international human rights law, which "guarantees that no one should be returned to a country where they would face torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and other irreparable harm."

These fears came true for the Yemenis when one of the returned men, Abdulqadir al-Madhfari, who had become "severely mentally disturbed" as a result of his treatment in the UAE, was seized by a Houthi militia and imprisoned in an unknown location, an outcome that should have persuaded the Omani authorities not to proceed with their own enforced repatriations.

The resettlement program in Oman

In particular contrast to the harrowing experiences of the men transferred to the UAE, Oman seemed to fulfil the U.S.’s best hopes regarding its "diplomatic assurances" in relation to the treatment of former prisoners. The Sultanate, as Ackerman explained, "granted them healthcare, housing, job training and some financial resources," although their lives were somewhat constrained in other ways. They were, for example, "unable to travel outside Oman, own businesses, or pursue higher education," but, "despite their diminished prospects, many of them found work, got married and had children."

Despite the evident success of the resettlement program, rumors of enforced expulsions began swirling earlier this year, and were reported by the Washington Post in May, when as Abigail Hauslohner described it, "Starting in January, Omani officials began calling the men into meetings where they explained that, come July, they would be stripped of their benefits and legal residency and would have to return to Yemen." In February, in what can now been seen as another sign of the Omanis’ changing attitudes, the two Afghans who were also resettled in Oman with the 28 Yemenis were sent home.

One of the resettled Yemenis, a father of three who spoke anonymously, because he told the Post that the Omani government had explicitly warned the men not to speak to the media, expressed the depth of his disappointment, and his feelings of betrayal. "It was a huge shock for all of us," he said, adding that, for many years, Oman had been "so supportive, so helpful. They told us: 'You are here to stay. This is your home.'" But now, he added, "They said, 'Your time is finished, and you have to leave.'"

Speaking to Spencer Ackerman more recently, another of the former prisoners said, "The Omanis treated us well until the day they informed us that we had to leave. On that day, officials threatened us, saying that if we chose to stay, we would lose housing, residency, healthcare and our children wouldn't be able to attend school. We would be left without jobs. One of them even warned, 'We are going to show you the other face,' implying that they would make our lives unbearable until we agreed to leave."

When Ackerman published his article, 26 of the 28 Yemenis had apparently all left Oman for Yemen, with one more to follow soon, although one other man didn’t survive the upheaval. Emad Hassan, who was just 45 and had been resettled in Oman in 2015, died last week, partly as a result of his long-term hunger striking for justice at Guantánamo, but also because of the stress caused by the proposed repatriation. Remembered as "a symbol of hope and resilience within Guantánamo" by his friend Mansoor Adayfi, he is "survived by his wife and two young daughters, who now face a future without his presence and support."

A composite image of Emad Hassan produced by CAGE.

The truly alarming position taken by a State Department spokesman

While the Omani authorities have refused to comment publicly about their decision to repatriate the Yemenis, the U.S. government’s position, as articulated in May by Vincent M. Picard, a spokesman for the State Department’s counterterrorism division, is startlingly irresponsible, from a human rights perspective, from the point of view of U.S. national security, and, perhaps most ominously, from its suggestion that resettlement programs were never meant to be permanent.

"In general, the United States government has never had an expectation that former Guantánamo detainees would indefinitely remain in receiving countries," Picard said, adding, with particular reference to Oman, that the Sultanate "is an excellent partner and fulfilled all aspects of the humane treatment and security assurances we agreed to for the detainees they have received. They have provided rehabilitation services and subsidies to former detainees for longer than required."

Picard’s position was criticized by Beth Jacob, the attorney for two of the Yemenis who were resettled in Oman, who stated, "My clients and I were told at the time that this was a permanent transfer. They were told to rebuild their new lives and make a home. They told me when they got to Oman, the Omanis welcomed them in and told them 'This is your new home.'" She added that the news about the enforced repatriations was "particularly surprising because Oman treated them so well. The welcome they received and the support they received from Oman was superb."

I know of only one previous instance when resettlements were revoked — in the cases of the two Libyans resettled in Senegal, who, when they were sent back to Libya, were told that the arrangements had only been for two years.

However, it is clear that Picard’s assertion needs to be challenged as robustly as possible, because it potentially opens the door for any government that resettled former prisoners at any time between 2009 and 2017 to claim that their responsibilities have also come to an end, and to send resettled prisoners back to their home countries, whether or not it is safe to do so.

This is why the actions of Senegal, of the UAE, and, now, of the Omani government, are so troubling, and why Picard’s comments are so shamefully irresponsible. If the resettlement programs were only meant to be temporary, where are the resettled men supposed to go?

Are we meant to think that the Congressional ban on sending men back to Yemen, based on security concerns that have been repeatedly raised by Republicans, and which the Biden administration is supposed to share, can be swept aside so long as the men in question are repatriated via a third country?

That is patently absurd, and yet it appears to be the position taken by Vincent Picard, disregarding both the U.S. security concerns based on stopping Yemenis from returning home to be potentially recruited into anti-U.S. terrorism, and the requirements, under international humanitarian law, that no one is forcibly sent from one country to another if that involves the risk of torture or of any other kinds of ill-treatment — the principle of non-refoulement, which was shamefully disregarded by the Senegalese government, and by the Emirati authorities, and which is now being disregarded by the Omanis.

As Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, who, until last year was the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms While Countering Terrorism, explained, with reference to the Yemenis in Oman, "Non-refoulement should be an absolute protection, because countries like Oman have a choice to protect these vulnerable torture survivors or not."

As she also explained, "Sending these men to Yemen puts them in profound danger. Yemen is a country in the midst of a brutal civil war, and is also being bombed by the United States and other allied countries. Sending former Guantánamo detainees, men who have been the victims of U.S. torture and ill-treatment back to Yemen flies in the face of the most fundamental human rights obligations of both Oman and the United States." For a more detailed assessment of the responsibilities of the U.S. and of host countries in resettling prisoners, see Ní Aoláin’s devastating report, published in 2022 after a visit to Guantánamo, and meetings with resettled prisoners.

As the example of Abdulqadir al-Madhfari shows, Ní Aoláin’s fears are well-grounded, and it is genuinely disturbing to see the principle of non-refoulement flouted so flagrantly by Oman, with not only the backing of the U.S., but also with, apparently, the additional suggestion that there are time limits on resettlements, as though men promised safety under "diplomatic assurances" that are meant to be binding can be arbitrarily discarded, and as though non-refoulement concerns are somehow optional.

What now?

When the Washington Post published its article back in May, I found it hard to believe that Oman, with its commendable track record on resettling the Yemenis, was seriously entertaining the prospect of forcibly repatriating them.

It seemed particularly unbelievable because, just a few weeks earlier, it had been revealed that the successor to Obama’s Special Envoys, the former ambassador Tina Kaidanow, who was appointed as the Special Representative for Guantánamo Affairs in August 2021, and is "responsible for all matters pertaining to the transfer of detainees from the Guantánamo Bay facility to third countries," had successfully negotiated the resettlement, in Oman, of eleven men still held at Guantánamo who have long been approved for release, but that those plans were put on hold because of the perceived "political optics" of releasing Guantánamo prisoners after the attacks in Israel by Hamas and other militants on October 7 last year.

The Post article, however, had an explanation. As an unnamed U.S. official explained, because there was "no requirement that the sultanate provide the men with permanent residency," one way of looking at it was that, by repatriating the 28 men, "In some ways, you could say they’re making room."

While this was as shamefully negligent of the Yemenis’ fundamental non-refoulement rights as Vincent Picard’s notion of time limits on resettlements, it seems, somehow, to have been accepted as an acceptable policy by both Oman and the U.S.

All eyes must now be on Yemen, in an attempt to establish that those sent back so recklessly and so lawlessly are safe, but what particularly stands out for me from this whole sordid story is the need for the State Department’s position to be robustly challenged.

I have no doubt that countries in the E.U. would balk at declaring that the men they took in for resettlement should now be repatriated, as lawyers would no doubt intervene to throw out these claims under the principle of non-refoulement. However, it leaves other men, resettled in other countries that might have less respect for international human rights law, in a much more vulnerable position, one that is fundamentally unacceptable, and which Vincent Picard and the State Department in general — up to and including the Secretary of State Antony Blinken — should be required to repudiate.

Former Guantánamo prisoners — and especially those resettled in third countries — already face uniquely challenging circumstances, as former "enemy combatants," uniquely without any fundamental rights, whose only guarantees of decent treatment are contained in secretive "diplomatic assurances" that have often — and demonstrably — been shamefully disregarded by their host countries.

For it now to be suggested that their situation is so precarious that they can be dispossessed and made stateless at will, or that they can be sent back to torture or ill-treatment in their home countries if their host countries think they can get away with it is absolutely unconscionable, and must not be allowed to prevail, even though, for former prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, who was resettled in Serbia in 2016, it reflects the reality of what he calls "Guantánamo 2.0." As he told Spencer Ackerman, "We live after Guantánamo a life of stigma and surveillance. The U.S. punished us for 15 years. The rest of the world punishes us for the rest of our lives."