Free the Guantánamo 16: A Message to President Biden as His Time Runs Out

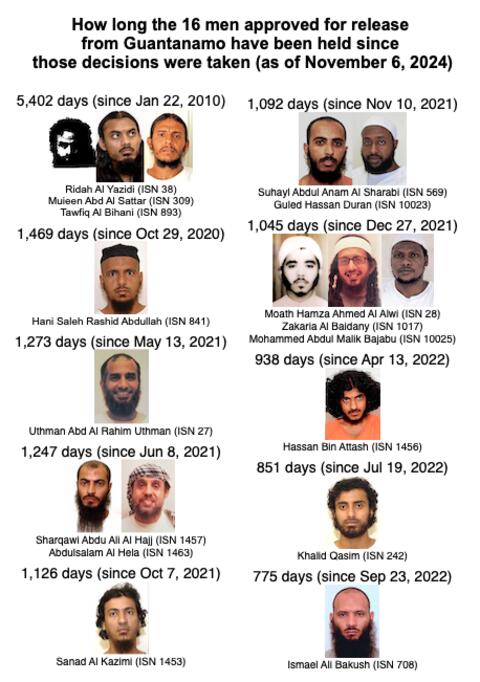

Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, who was resettled in Serbia in 2016, holds up the "Free the Guantánamo 16" poster showing the 16 men still held, despite being approved for release, on November 6, 2024.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout the rest of 2024, and into 2025. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, November 13, 2024

As the dust settles on last week’s Presidential Election, and the U.S. and the rest of the world wait anxiously to see quite what Donald Trump has planned for the future, one policy decision seems unlikely to offer any surprises.

As in his first term in office, Trump — who is very evidently Islamophobic (as we all ought to recall from his Muslim ban in 2017), and is the head of a debased Republican Party that contains numerous screamingly hysterical enthusiasts for the continued existence of the prison at Guantánamo Bay — will almost certainly seal Guantánamo shut, as he did in his first term, refusing to set any prisoner free unless, by some miracle, they are required to be freed through legal means.

For the 30 men still held at Guantánamo, the situation is remarkably similar to that which faced President Obama eight years ago, as the news sank in that Hillary Clinton would not be taking over from him, and that Donald Trump would soon be inheriting Guantánamo, which he had bullishly promised to "load up with some bad dudes." In the end, that threat never materialized, as, even in Trump’s inner circle, enough common sense existed to recognize that Guantánamo was an unsalvageable legal mess, and that, for any "bad dudes" that Trump managed to round up, prosecuting them in federal courts would be the only sensible option.

For Obama and his advisers, still vaguely able to be stung by accusations that he had promised to close Guantánamo but had failed to do so, his last two months in office involved a whirlwind of activity regarding Guantánamo, as 19 men in total — out of the 60 still held at the time of Trump’s victory — were released.

These men had all been unanimously approved for release by high-level government review processes established under Obama — the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which, in 2009, administratively reviewed the cases of the 240 prisoners inherited from George W. Bush, and decided whether to approve them for release (two-thirds of them), or to recommend them for prosecution or for ongoing imprisonment without trial, and its follow-up, the parole-style Periodic Review Boards, which began reviewing prisoners’ cases in November 2014.

Most of these 19 men had to be resettled in third countries, because of provisions inserted into the annual National Defense Authorization Act, which prevented — and still prevent — the repatriation of prisoners to certain proscribed countries, including, in particular, Yemen.

The urgent need for resettlements in President Biden’s last months in office

Eight years on, President Biden faces a similar situation. Having freed ten men (to add to the one man who managed to escape from Guantánamo under Trump), 16 of the 30 men he still holds have been unanimously approved for release by high-level government review processes — mostly the PRBs, and mostly on his watch.

This time around, however, there is a conspicuous lack of a sense of urgency within the Biden administration, as well as, sadly, a less welcoming environment globally for resettling former Guantánamo prisoners than existed in the Obama years.

While Obama created a high-level role within the State Department, the Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, to oversee prisoner releases, Biden’s replacement role, the Special Representative for Guantánamo Affairs, who was "responsible for all matters pertaining to the transfer of detainees from the Guantánamo Bay facility to third countries," was given less high-level backing.

Created in August 2021, the role was given to former Ambassador Tina Kaidanow, who, nevertheless, managed to negotiate a resettlement plan with Oman, which had taken in 28 prisoners, mostly Yemenis, under Obama.

Shamefully, although a plane was sent to Guantánamo last October to take eleven of the 16 cleared men for resettlement in Oman, more senior officials — presumably Biden and Antony Blinken, the Secretary of State — decided that the October 7 attacks in southern Israel by Hamas and other militants meant that the "political optics" had shifted, and that it was not appropriate for the resettlement to go ahead.

No new date was set for the resettlement, and, because the decisions to approve prisoners for release are purely administrative, no legal mechanism exists whereby these men can ask a judge to order the government to release them.

Their freedom, as the Center for Constitutional Rights memorably declared in 2022, is reliant not upon the law, but on the "discretion and grace" of those holding them, a situation that is so arbitrary that it serves only to confirm that, despite legal challenges and review processes, nothing has fundamentally changed at Guantánamo, and that men held fundamentally without any rights whatsoever when the prison opened are still in that same predicament nearly 23 years later.

In August, there was even more alarming news regarding the resettlement plans, as Oman expelled the 26 Yemenis it had taken in between 2015 and 2017 — who had mostly settled in well, finding work, reuniting with their families, and in some cases marrying and having children — and repatriated them to Yemen, in many cases unwillingly.

This was unacceptable under international humanitarian law, because it violated the non-refoulement obligation on all countries, which requires them not to send people back to countries where they face torture or other forms of ill-treatment, but, more tellingly for the U.S., it also contravened the obligation, under the NDAA, not to send Yemenis from Guantánamo back to their home country for reasons of national security.

Despite this, when the plans were first leaked in May, Vincent M. Picard, a spokesman for the State Department’s counterterrorism division, claimed, outrageously, that, "In general, the United States government has never had an expectation that former Guantánamo detainees would indefinitely remain in receiving countries."

Picard’s assertion conspicuously failed to address where released prisoners were supposed to go if their resettlements were suddenly terminated, and its cavalier disregard for both the non-refoulement obligation and the NDAA provisions regarding proscribed countries has only muddied the waters when it comes to resettling the men awaiting release from Guantánamo.

President Biden’s legacy

It is to be hoped, however, that some sort of successful revival of the resettlement plan can be negotiated with Oman, because otherwise the men approved for release, who have already been waiting for between two and four years since the decisions to approve them for release were taken — and in three outlying cases for nearly 15 years — will be trapped at Guantánamo for another four years.

A poster showing how shamefully long, as of November 6, the 16 men approved for release had been waiting to be freed since those decisions were taken.

As President Biden prepares to leave office, he has a chance to salvage something of a legacy by taking decisive action to address the outstanding injustice of the men still held at Guantánamo despite having been long approved for release.

If he does so, it will be a small measure of success when contrasted with what will undeniably be the main component of his legacy — his unforgivable indulgence of, and support for Israel’s unending genocidal assault on the Gaza Strip — but it will be an act of huge significance.

Domestically, Guantánamo has been all but forgotten, but internationally it remains a scar on U.S. claims to have any respect whatsoever for the laws that it claims to uphold. 12 of the 16 men approved for release had those decisions taken under Biden himself. If he fails to free them, leaving them to rot for another four years under Donald Trump, his indifference will not only constitute a personal failure to properly tackle the bitter and corrosive legacy of Guantánamo; it will also be noticed around the world as yet another example of chronic U.S. dysfunction and dishonesty.

Finding new homes for these men will also be a suitable tribute to the efforts of Tina Kaidanow, who sadly died of a heart attack on October 16, stymied to the last in her efforts to deliver some measure of justice to Guantánamo’s long-suffering "forever prisoners."

What can we do?

For anyone wanting to help to exert pressure on the Biden administration, I encourage supporters to look at the 24 Senators and 75 members of the House of Representatives — all Democrats — who wrote to Biden in 2021, urging him to take decisive steps towards the prison’s closure by freeing everyone not charged with a crime, and facilitating plea deals for those charged in the military commissions.

If any of these lawmakers represent you, please do consider getting in touch with them to urge them to come together once more to call for urgent action from the Biden administration in its dying days, in particular by urging them once more to press for the release of the 16 men whose ongoing imprisonment they recognized as unconscionable three years ago.

If you wish, you can also address the plea deals that they called for, and urge the administration not to oppose the plea deals that were agreed this summer with three of the five men charged in connection with the 9/11 attacks. Immediately afterwards, defense secretary Lloyd Austin shamefully attempted to cancel the deals, but the military judge at Guantánamo has just reinstated them.

It is important, for any lingering notions of justice, for the plea deals to be allowed to stand, and for no further action to be taken by the administration to exert undue command influence on the prosecutors and defense teams at Guantánamo — and the military official appointed by Austin to oversee them — who all concluded, nearly three years ago, that the use of torture had made successful prosecutions impossible, and who have been working assiduously ever since to arrange the plea deals as the only viable way forward.

Most of all, though, I cannot stress enough how important it is that any lawmakers with a conscience need to call for an end to the legal purgatory of the men approved for release, and not to allow them to be entombed at Guantánamo for another four years under Donald Trump.

Note: For further clarification, of the 30 men still held at Guantánamo, beyond the 16 approved for release, three are still held indefinitely without charge or trial, having had their ongoing imprisonment repeatedly recommended by PRBs, three have agreed plea deals in the military commissions, six face active charges, one was removed from the 9/11 trial because a DoD Sanity Board concluded that he was unfit to stand trial (his status, as a result, is completely unknown), and one other man is beginning the 17th year of a life sentence, after a one-sided trial in 2008, in which he refused to mount a defense, with most of those years to date spent in almost complete isolation.